Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

Home / Who Were The Loyalists?

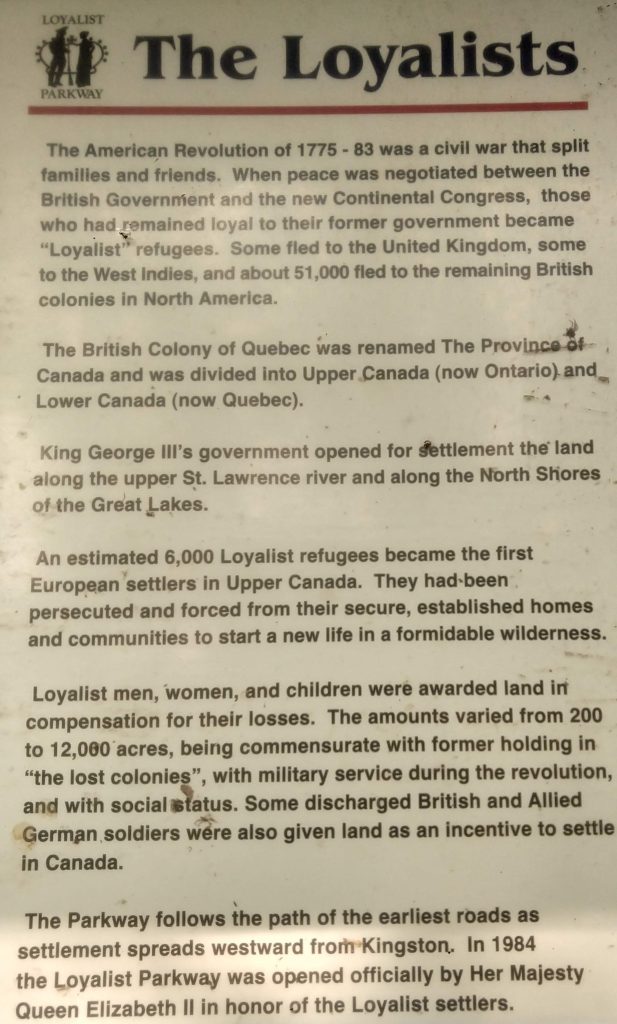

Once there were the Canadiens (Indigenous First Nations groups and the descendants of New France settlers inhabiting the Province of Quebec). Then there were Loyalists (those who came to British North America – NS, NB, the Province of Quebec) after the war of American Independence.

The Canadiens and the Loyalists came together to become Canadians.

This is how it happened: After the American War of Independence (1775 -1783) the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. Loyalist soldiers and civilians migrated largely from New York state and Northern New England where they were being violently persecuted for supporting the British. These formed the NUCLEUS of our current Canadian society.

The Loyalists merged with the Canadiens to form the new ‘Canada’.

These political refugees came from every social class and from all of the New England states. 10,000 went to Quebec (Upper and Lower Canada) and between 35,000 to 40,000 went to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Wikipedia). These were settled by various criteria like ethnicity, religion or by the regiments in which they served. To encourage settlement growth, Britain gave them 200 acres per person. The Loyalists settlements initiated the reorganization of the British colonies of Nova Scotia and Quebec.

Nova Scotia was divided into New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, while the Province of Quebec was divided into Upper and Lower Canada.

These Loyalists wanted to maintain their British system of laws and government. They therefore petitioned Britain to allow them to maintain the parliamentary system of government they were accustomed to in the US, as opposed to the French civil laws and government of the British colony called ‘The Province of Quebec’. In response, the Treaty of Separation of Quebec into two provinces (Upper & Lower Canada) also took place in 1783.

Britain separated the Province of Quebec into English-speaking Upper Canada and French-speaking Lower Canada, thus allowing French speakers to maintain their language, laws and religion.

Lord Dorchester (Governor of Quebec and Governor General of British North America) on behalf of the Crown, recognized that this first wave of Loyalists, even BEFORE the Treaty of Separation of 1783, were committed to keeping the ‘Unity of the Empire’ and coming under British protection. They were therefore given the special designation of UE (Unity of Empire) to be inherited by their descendants in perpetuity.

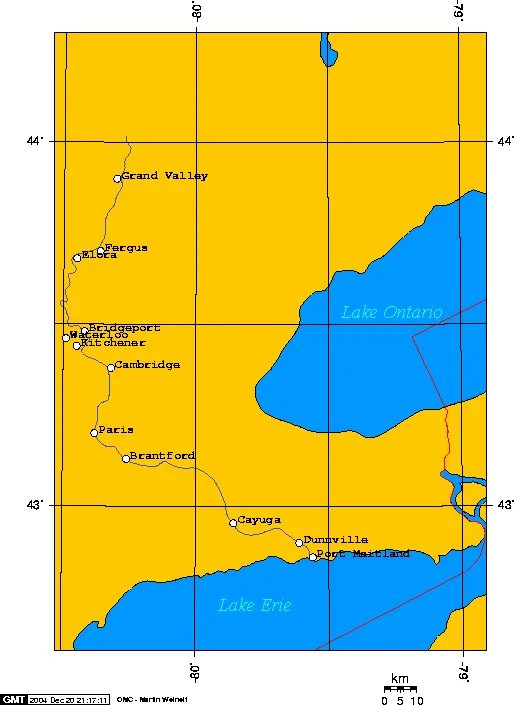

It is important to note here that MOST of the Iroquois Six Nations of upstate New York had sided with the British in the war. Because they were loyal to Britain, they were expelled from New York and the other states. They were granted lands along the Grand River – the largest First Nations Reserve in Canada – and in the Bay of Quinte. Those who settled by the Grand River were led by the Mohawk, Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant.

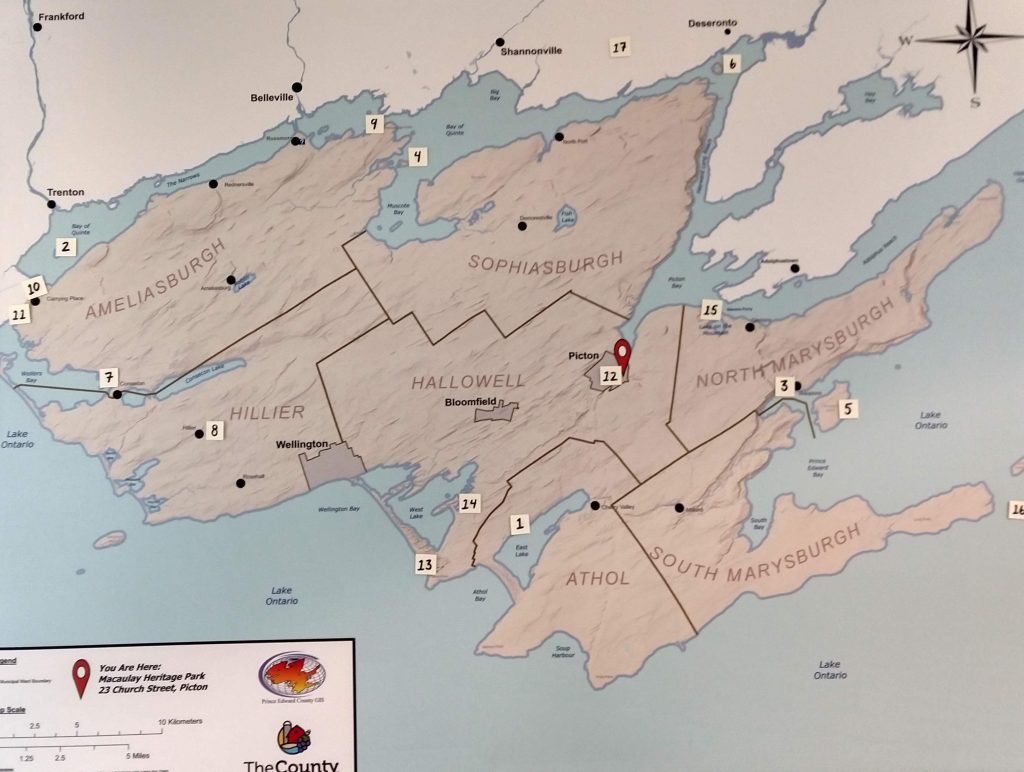

A smaller group of Mohawks led by Captain John Deserontyon Odeserundiye settled closer to the Bay of Quinte in Prince Edward County. Governor Frederick Haldimand purchased a tract of land from the Mississaugas to settle about 200 Mohawks in the Bay of Quinte. This is currently known as Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. The town of Deseronto is named in honour of Colonel John Deserontyon.

The Loyalists arrived in Canada in two waves. The ‘initial’ Loyalists came around 1776 before the separation of the Province of Quebec, and the ‘late’ Loyalists came after the Separation Treaty was signed in 1783.

In the 1790’s, the Leut.-Governor of Upper Canada, to encourage settling of the new colony, offered land and lower taxes to Americans to move to Upper Canada. All told, by the time the War of 1812 rolled around, there were 110,000 Loyalists in Upper Canada. 20,000 were initial Loyalists, 60,000 were later immigrants and 30,000 were immigrants from Britain and their descendants. After that, immigrants came because of land grants.

Land along the Grand River became one of the largest Indigenous Reserves in Canada.

It was given by Governor John Graves Simcoe to the Mohawks led by Thayendanega also known as Joseph Brant.

His name is memoralized by the town of Brantford and the County of Brant.

Prince Edward County in the Bay of Quinte, was settled by Loyalists and is known as ‘Loyalist Country’.

The Indigenous Reserve is named Tyendinaga Mohawk Reserve probably after Joseph Brant.

The town of Deseronto is named in honour of Colonel John Deserontyon who chose this location for the Natives he led.

Black Loyalists, 3,500 of them, were free black slaves who were encouraged to join the British army during the Revolution as a means of freedom from slavery in the US. Most of them settled in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Apart from facing the regular challenges that all Loyalists faced (delays in accessing their promised land grants), they faced the added challenge of racial discrimination on two levels.

Firstly, delivery of their land grants was very slow so they could not settle. Army oficers and previously wealthy landowners were given land first. By the time it was the turn of the black Loyalists, the acreages they were given were smaller, poorer and more remote than their white counterparts. Many of the black Loyalists were refugees from the south where the climate was more forgiving than the harsh winters.

Many of them constructed ‘pit houses’ to survive the harsh winter. A kind of ‘foundation hole’ was dug out of the ground, about 20 inches deep and as wide and as long as a family desired. Then a steep roof was constructed over it to keep the rain and snow from filling the hole.

In 1792, 1,300 black Loyalists left Canada to establish Freetown in the new British colony of Sierra Leone.

Secondly, they were willing to accept lower wages for the few available jobs than their white counterparts. In July of 1784, riots erupted in Shelburne when white Loyalists clashed with black Loyalists.

Many Loyalists left substantial property in the United States because they were expelled, or suffered violence or threats of violence. This included white and Indigenous Loyalists. Britain sought restoration for this loss of property, especially for the First Nations who had to leave their homes which they enjoyed for many generations. Even though there was a proclamation called Jay’s Treaty, Congress did not implement the terms.

Slavery was still legal at the time of the American Revolution. Loyalists from all thirteen colonies of the US brought their slaves with them to Canada. The record shows that there were 2,000 slaves in British North America: 500 were in Upper Canada (Ontario), 300 in Lower Canada (Quebec) and 1,200 in the Maritime Provinces.

A unique situation arose in the Maritimes. There were more slaves than the free population – and there were no plantations. Eventually, many of these slaves were freed, and, together with the free black Loyalists, many went to settle the new colony of Sierra Leone. In 1790, the British Parliament passed a law assuring wealthy, slave-owning immigrants from the US that they could keep their slaves as property in Canada.

However, in 1793, the first Parliament of Upper Canada passed an anti-slavery law, becoming the first ‘country’ in the world to make slavery illegal. It banned the importation of slaves and gave emancipation at age 25 to all children born of slave women.

The slave trade was eventually abolished across the British Empire in 1803.

The bronze statue depicts a family of Loyalists at the moment they have drawn their lot number from the government surveyor. They are looking forward with satisfaction and keenness and a little curiosity to the location of their new home in Canada after the turmoil of many years of warfare and after having lost all of their worldly possessions.

This image eventually attained national fame when a drawing of the monument was featured on a Canadian postage stamp.

The words on this monument say:

This monument is dedicated to the lasting memory of the United Empire Loyalists who, after the declaration of independence, came into British North America from the seceded American colonies and who, with faith and fortitude, and under great pioneering difficulties, largely laid the foundations of this Canadian nation as an integral part of the British Empire. Neither confiscation of their property, the pitiless persecution of their kinsmen in revolt, nor the galling chains of imprisonment could break their spirits or divorce them from a loyalty almost without parallel.

“No country ever had such founders – No country in the world – No, not since the days of Abraham” — Lady Tennyson

The United Empire Loyalists were distinguished for their devotion to principle, for their valour in battle during the American revolution and for their loyalty and bravery in the War of 1812-1814 in defense of Canadian homes and hearths.

They set the stamp of their character in the institutions of this country and handed them on to succeeding generations glorified by their sacrifices, enriched by their labours and made sure by their indomitable spirit. Dedicated to the Glory of God; Erected by Mr. and Mrs. Stanley Mills of Hamilton

In Grateful Memory of Their United Empire Loyalists Forebears and Connections: The Davis, Gage, Hesse, Howell, Mills and Willson Families

Unveiled Empire Day, May Twenty-Third, Nineteen Hundred and Twenty-Nine

For The Unity of Empire

The United Empire Loyalists, believing that a monarchy was better than a republic, and shrinking with abhorrence from a dismemberment of the Empire, were willing, rather than lose the one and endure the other, to bear with temporary injustice.

Taking up arms for the King, they passed through all the horrors of civil war and bore what was worse than death, the hatred of their fellow-countrymen, and, when the battle went against them, sought no compromise, but, forsaking every possession excepting their honour, set their faces toward the wilderness of British North America to begin, amid untold hardships, life anew under the flag they revered.

“They drew lots for their lands and with their axes cleared the forest and with their hoes planted the seed of Canada’s future greatness.” — Elizabeth Bowman Spohn

https://uelac.ca/monuments/hamilton-loyalist-plaque/

This plaque states:

In lasting memory of the United Empire Loyalists who preferred to remain British subjects and come to Canada in large numbers immediately following The American Revolution of 1776 and the signing of the Peace Treaty in 1783.

On this site in 1785 was erected one of the first log houses in the district by a Loyalist pioneer Col Richard Beasley who on June 11th and 12th 1796 here entertained Lt. Colonel John Graves Simcoe the first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada and Mrs Simcoe.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of