Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

Home / War of 1812 – Lake Ontario’s Story

Many stories have been told about the War of 1812. For newcomers to Canada, and the ‘not-so-new Transplanted Canadians’, this was a war fought between the United States and Canada during a period of history where distrust was the name of the game.

To put it in a greatly simplified context, the American War of Independence was fought when 13 British Colonies no longer wanted to be ruled from afar. It is almost like if they did not want to support what appeard to them as ‘unreasonable, out-of-touch absentee landlords’. They wanted control of their own destinies and resources. So they rebelled and fought against the British, gaining their own sovereignty and choosing a Republican form of government over a parliamentary democracy like we have in Canada.

Upper and Lower Canada, PLUS New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were forged out of that war for independence. You can read some of that story in this article about The Loyalists.

The British colonies north of the US (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper Canada and Lower Canada) viewed their neighbours to the south with suspicion because it was no secret that they wanted to get Britiain OUT of North America. Their suspicions became a reality in 1812, about 19 years after the War of American Independence.

Much has been written about this war. Movies AND documentaries have been produced about it. As far as I know, the jury is still out with regard to WHO won that war, not that it matters anymore. The object of this article is to let the historic markers and plaques speak for themselves.

Most of the information on this page is quoted directly from the plaques, so you know what they say.

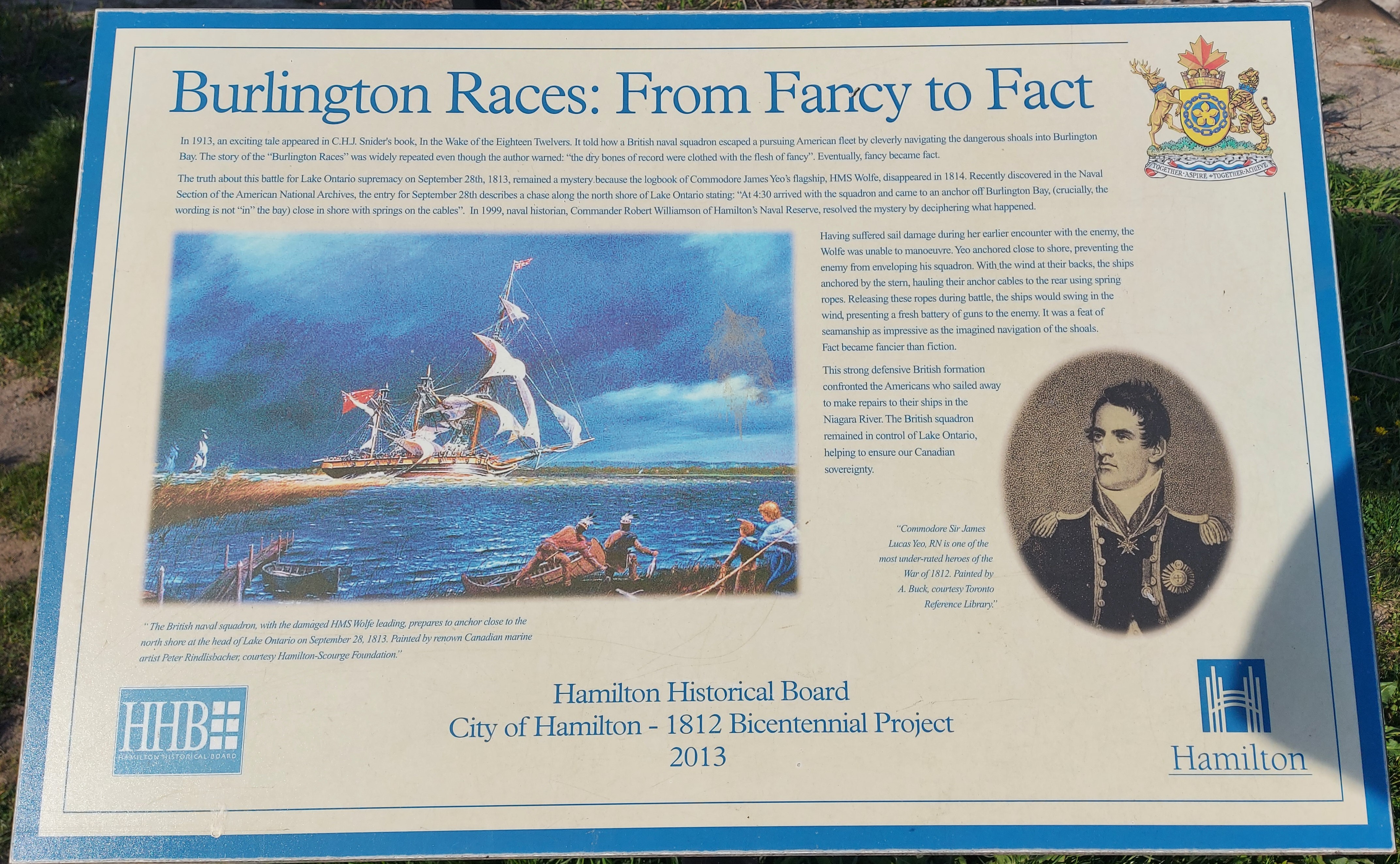

Burlington Races: From Fancy to Fact

In 1913, an exciting tale appeared in C.H.J Snider’s book, In the Wake of the Eighteen Twelvers. It is told how the British naval squadron escaped a pursuing American fleet by cleverly navigating the dangerous shoals in the Burlington Bay. The story of ‘The Burlington Races’ was widely repeated even though the author warned that “the dry bones of record were clothed with the flesh of fancy”.

Eventually, fancy became fact. The truth about this battle for Lake Ontario supremacy, on September 28 1813 remained a mystery because the logbook of Commodore James Yeo’s flagship HMS James Wolfe disappeared in 1814.

Recently discovered in the Naval Section of the American National Archives, the entry for September 28th describes a chase along the North shore of Lake Ontario stating: “At 4.30, arrived with the squadron and came to an anchor at Burlington Bay (crucially the wording is not ‘in’ the Bay) close to shore with springs on the cables”. In 1999, naval historian Commander Robert Williamson of Hamilton’s Naval Reserve, resolved the mystery by deciphering what happened…

Having suffered sail damage during her earlier encounter with the enemy, the Wolfe was unable to manoevre. Yeo anchored close to the shore preventing the enemy from enveloping his squadron. With the wind at their backs the ships anchored by the stern, hauling their anchor cables to the rear using spring ropes.

Releasing these ropes during battle, the ships would swing in the wind presenting a fresh battery of guns to the enemy. It was a feat of seamanship as impressive as the imagined navigation of the shoals. Fact became fancier than fiction. This strong defensive British formation confronted the Americans who sailed away to make repairs to their ships in the Niagara river. The British squadron remained in control of Lake Ontario, helping to ensure our Canadian sovereignty. (As quoted on the plaque)

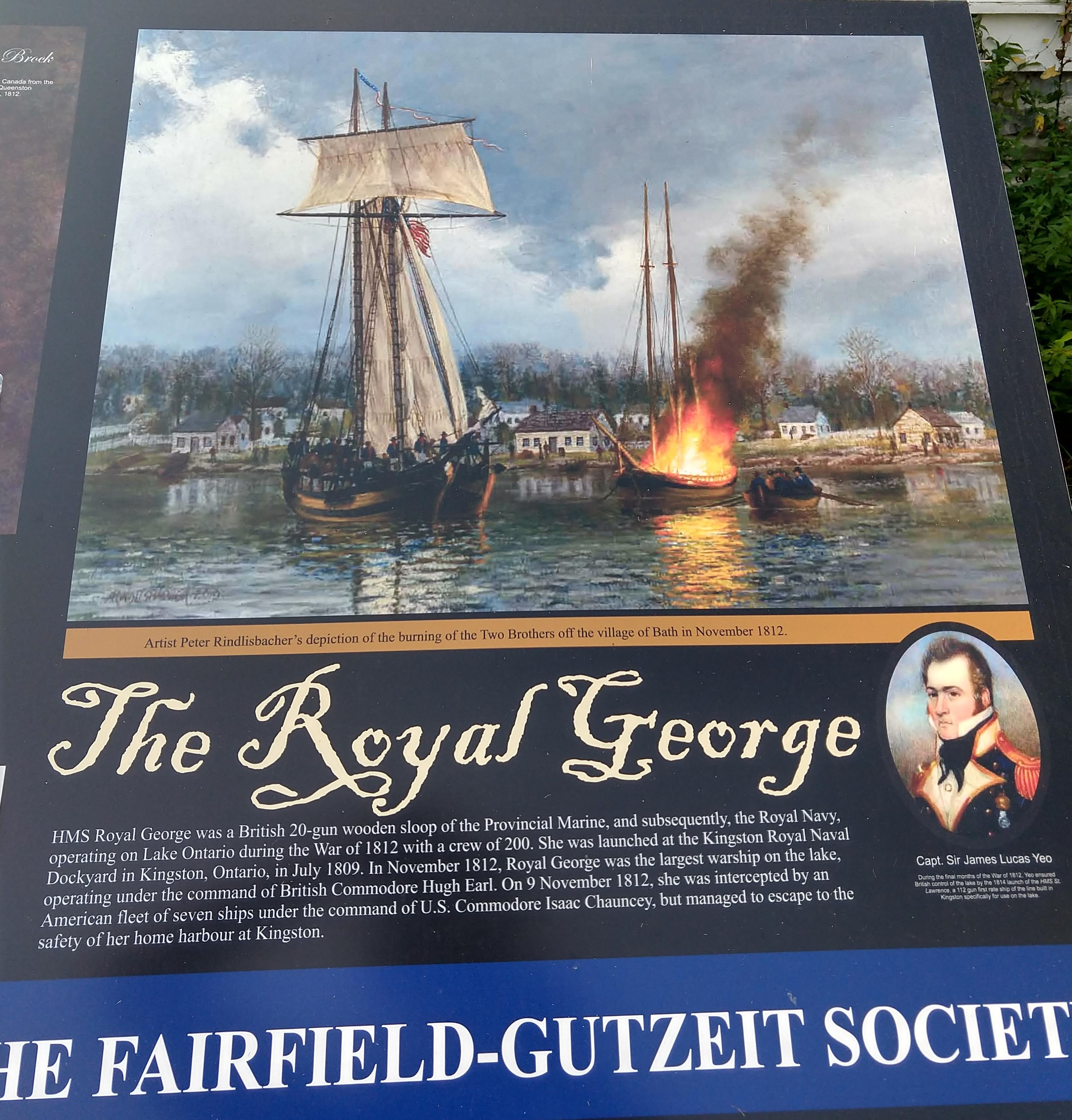

The Royal George

The Royal George was a British 20-gun wooden sloop of the Provincial Marine and subsequently the Royal Navy operating on Lake Ontario during the War of 1812 with a crew of 200. She was launched at the Kingston Royal naval Dockyard in Kingston Ontario in July 1809. In the War of 182, Royal George was the largest warship on the lake operating under the command of British Commodore Hugh Earl.

On 9 November 1812, ahe was intercepted by an American fleet of 7 ships under the command of US Commodore Isaac Chauncy but managed to escape to the safety of her home harbour in Kingston.

The Second Invasion of York 1813

On the morning of July 31, 1813, a US invasion fleet appeared off York (Toronto) after having withdrawn from a planned attack on British positions at Burllington Heights.

That afternoon 300 American soldiers came ashore near here. Their landing was unopposed; there were no British regulars in town and York’s militia had withdrawn from further combat in return for its freedom during the American Invasion three months earlier. The invaders seized food and military supplies then re-embarked.

The next day they returned to investigate collaborators’ reports that valuable stores were concealed up the Don River. Unsuccessful in their search the Americans contented themselves with burning military installations on nearby Gibraltar Point before they departed. (As quoted on the marker).

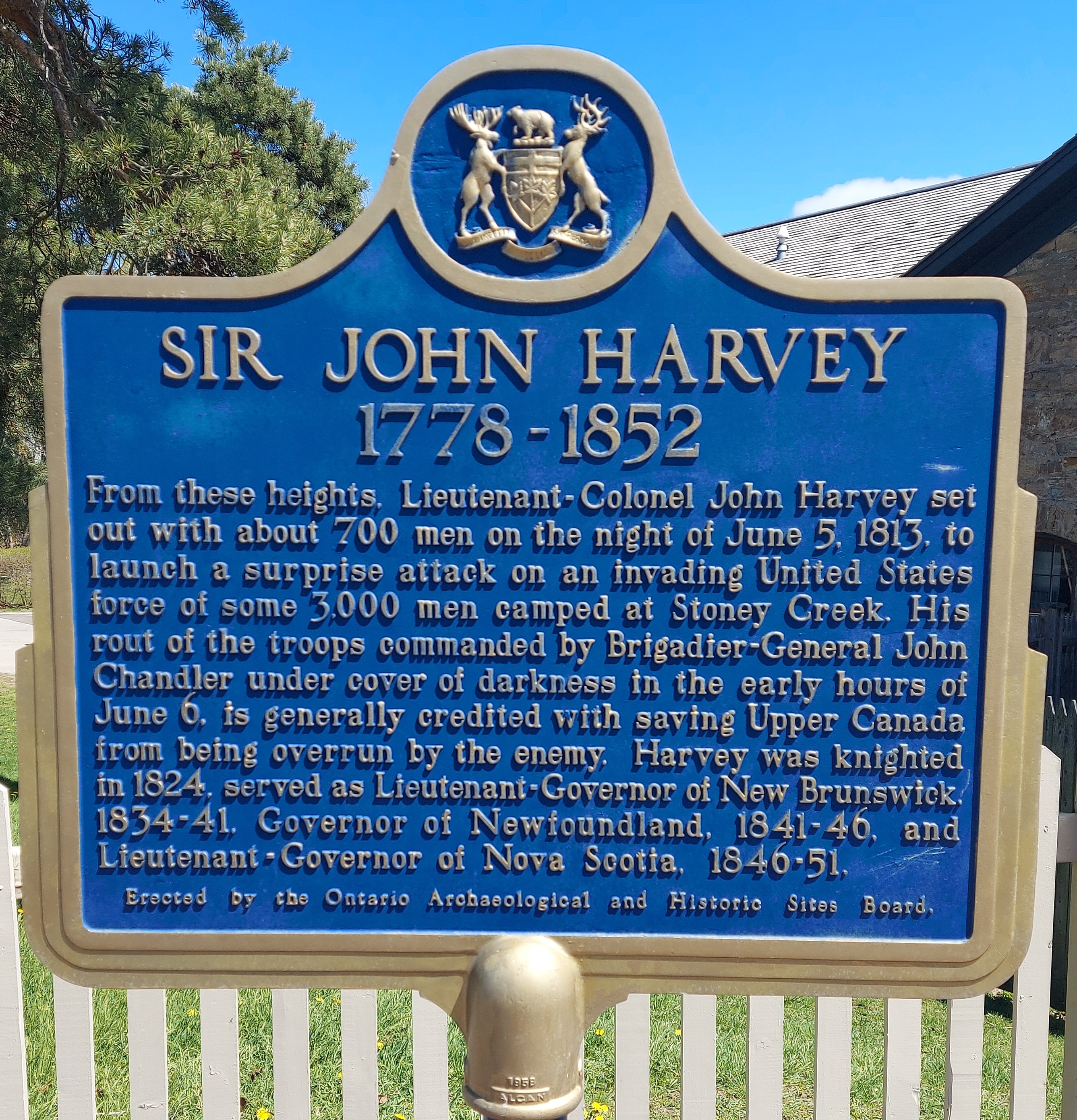

Sir John Harvey (at Dundurn Castle)

From these heights, Lieutenant – Colonel John Harvey set out with about 700 men on the night of June 5, 1813 to launch a surprise on an invading United States force of 3,000 men camped at Stoney Creek.

His rout of the troops commanded by Brigadier-General John Chandler under cover of darkness in the early hours of of June 6th is generally credited with saving Upper Canada from being overrun by the enemy.

Harvey was knighted in 1834, served as the Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick in 1834-41. Governor of Newfoundland 1842-46 and Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia 1846-51. (As quoted on the marker).

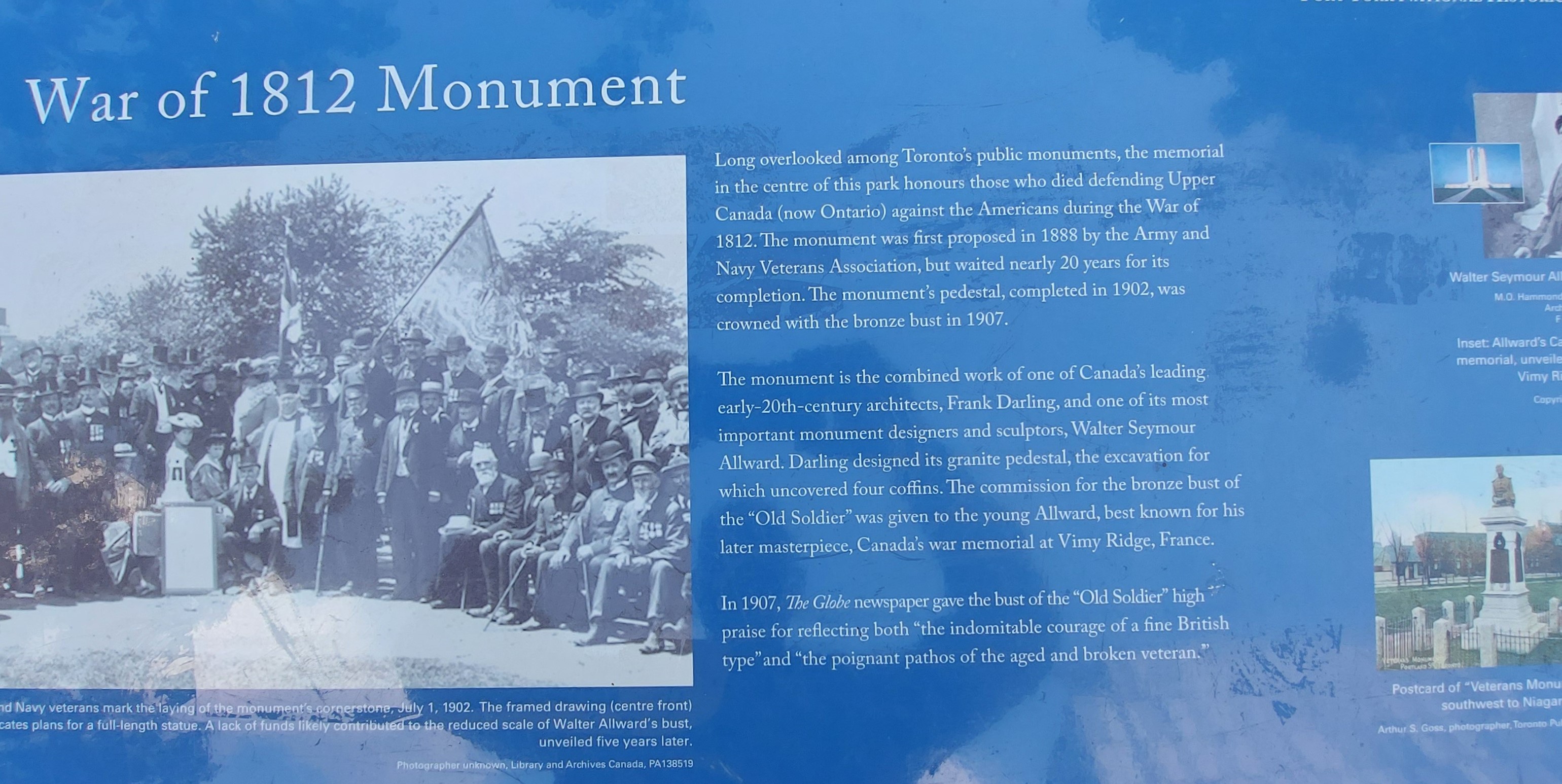

Monument Plaque in Coronation Park

Long overlooked among Toronto’s public monuments, the memorial in the centre of this park (Coronation Park) honours those who died defending Upper Canada (now Ontario) against the Americans during the War of 1812. The monument was first proposed in 1888 by the Army and Navy Veterans Association, but waited 20 years for its completion. The monument’s pedestal, completed in 1902 was crowned with the bronze bust in 1907.

The monument is the combined work of one of Canada’s leading early 2oth-century-architects, Frank Darling, and one of its most important monument designers and sculptors Walter Seymour Allward.

War of 1812 Monument

Frank Darling designed its granite pedestal, the excavation for which uncovered four coffins. The commission for the bronze bust of ‘The Old Soldier’ was given to the young Allward, best known for his later masterpiece, Canada’s war memorial at Vimy Ridge, France.

In 1907, The Globe newspaper gave the bust of ‘The Old Soldier’ high praise for reflecting both ‘the indomitable courage of a fine British type’ and ‘the poignant pathos of the aged and broken veteran’. (As quoted on the plaque in Coronation Park).

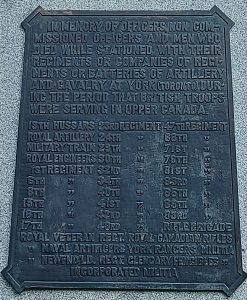

One of the four inscribed plaques on The Old Soldier

This plaque says: In memory of officers, non-commissioned officers and men who died while stationed with their regiments or companies of regiments or batteries of artillery and cavalry at York (Toronto) during the period that British troops were serving in Upper Canada. It goes on to list all the different companies of officers who fought in the War of 1812.

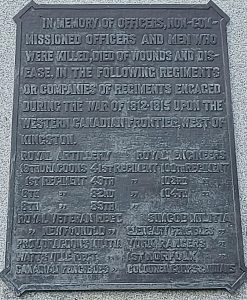

This second face of the monument says: In memory of officers and non-commissioned officers and men who were killed, died of wounds and disease, in the following regiments or companies of regiments engaged during the War of 1812-1815 upon the Western Canadian frontier West of Kingston. It goes on to list all the different companies of officers who fought in the War of 1812.

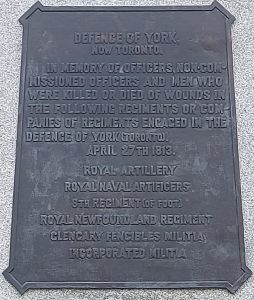

The third plaque of this monument states:

Defence of York, Now Toronto

In memory of officers, non commissioned officers and men who were killed or died of wounds in the following regiments or companies of regiments in the defence of York (Toronto).

April 27 1813.

Royal Artillery; Royal Naval Artificers

8th Regiment (of foot); Royal Newfoundlamnd Regiment

Glengarry Fencibles Militia; Incorporated Militia

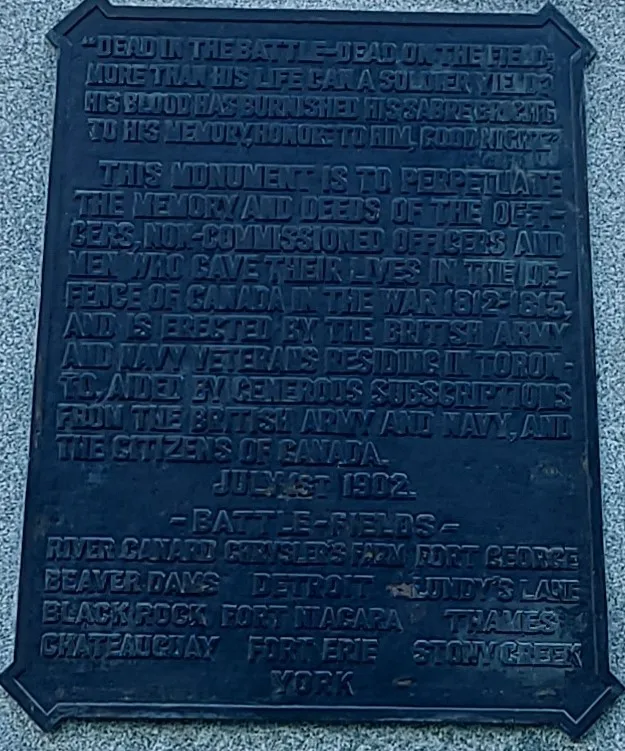

This is written on the fourth plaque on the statue:

Dead in the battle – Dead in the field

More than his life can a soldier yield?

His blood has burnished his sabre bright

To his memory honour – To him good night

This monument is to perpetuate the memory and deeds of the officers, non commissioned officers and men who gave their lives in defence of Canada in the war 1812 – 1815 and is erected by the British Army and Navy and the citizens pof Canada.

July 1st 1902.

– Battlefields –

River Canard; Chrysler’s Farm; Fort George;

Beaver Dams; Detroit; Lundy’s Lane; Black Rock;

Fort Niagara; Thames; Chateauguay; Fort Erie;

Stony Creek; York

These historical plaques and markers tell stories of Canada which you may/may not find in textbooks. As my husband and I travel around Ontario, we take pictures of these treasure troves when we find them, whether at local museums, or just driving along the highways.

If you look back at recent articles, you will find plaques about Yonge Street Toronto, Brantford/Paris area, The Loyalists, and the War of 1812 as it was fought on Lake Huron.

For those who have moved to Canada from other places, this is a reminder that history matters. We can’t understand the present without looking back to see where we came from and where we are going.

We are glad you have joined us on this journey of discovery. Don’t forget to scroll right to the bottom of this page and click the green button which says, ‘Get Articles In Your Inbox’, if you want to get these articles as soon as they are posted.

Author’s Note: Lynette is the owner of ChristianRoots Canada. Blogger. Publisher. Course Creator. Passionate about Canadian History from the perspective of God’s Providence.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of