Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

Home / War of 1812 – Rescued By Native Allies

Have you ever heard the phrase, ‘enquiring minds want to know?’ That’s ME. I am a ‘Transplanted Canadian’ who grew up in the West Indies and immigrated to Canada many moons ago. I taught Canadian History to homeschoolers but some of the information did not make complete sense. For example, the Quebec question still baffles me, the Native issue is convoluted and complicated, and more recently, writing about the War of 1812 showed me how much I did not know what I did not know.

I have now come to think that discovering Canadian History is like doing a puzzle. I learn about Canada’s history in abstract terms. Then, if and when I visit historic sites and take hundreds of photos, light bulbs go on in my head as bits and pieces of ‘theory’ come to life. THIS is what happened to me when I eventually got around to examining the information in the photos I have collected about the War of 1812.

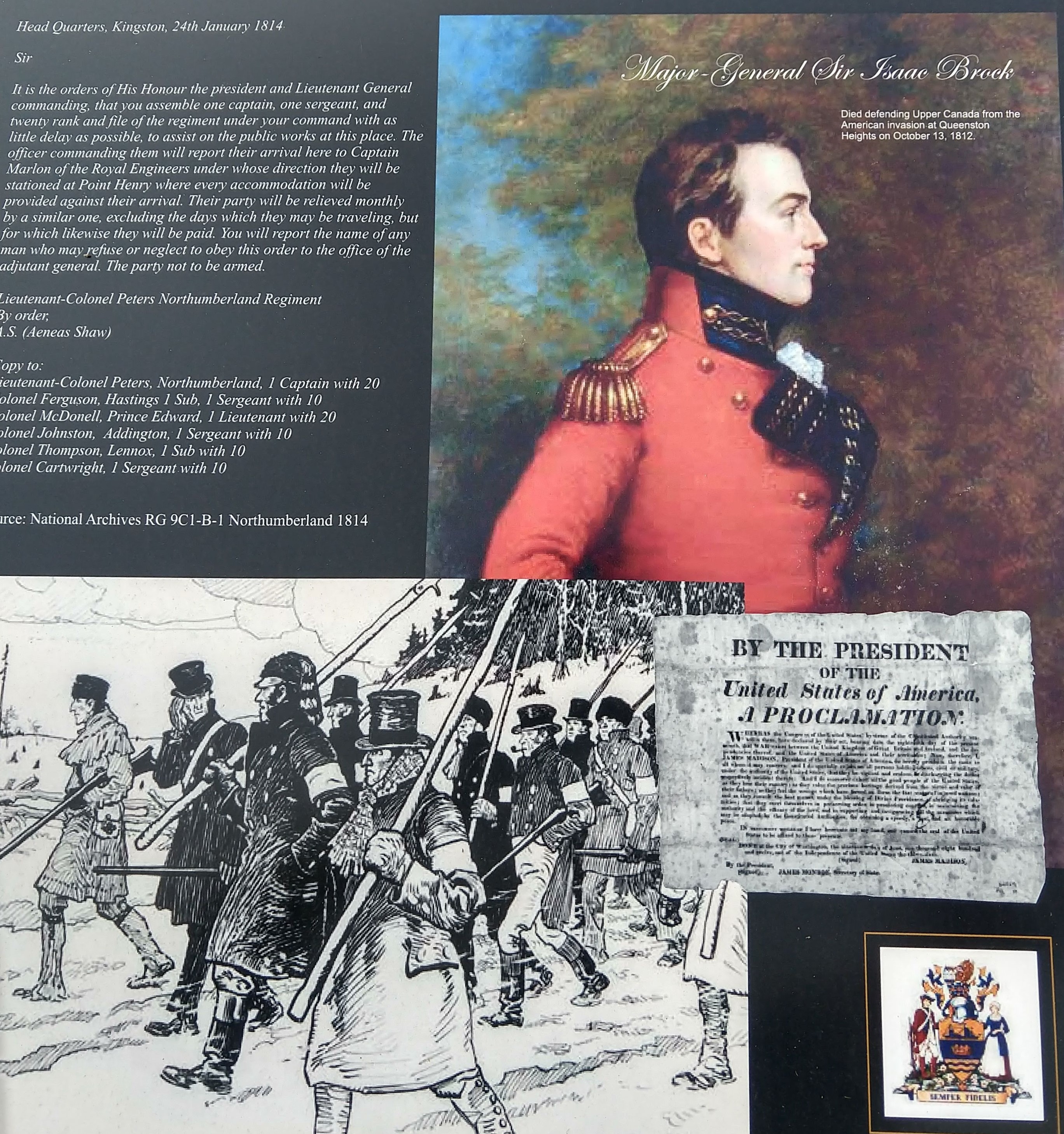

Isaac Brock was a soldier and a statesman who gave his life to ensure the survival of the Canadas (Upper Canada and Lower Canada) when those in the Legislative Assembly failed to see the real danger of being absorbed into the American republic. His legacy deserves a much longer article. But consider this account written about the attitude of the citizens and Legislature of Upper Canada:

Isaac Brock was a soldier and a statesman who gave his life to ensure the survival of the Canadas (Upper Canada and Lower Canada) when those in the Legislative Assembly failed to see the real danger of being absorbed into the American republic. His legacy deserves a much longer article. But consider this account written about the attitude of the citizens and Legislature of Upper Canada:

“He again met the Upper Canada legislature on 27 July, and again found it lukewarm; it was still unwilling to suspend habeas corpus. On the 29th he wrote to the adjutant general at headquarters in Montreal: “My situation is most critical, not from anything the enemy can do, but from the disposition of the people – the population, believe me is essentially bad – A full belief possesses them all that this Province must inevitably succumb – This prepossession is fatal to every exertion – Legislators, Magistrates, Militia Officers, all have imbibed the idea, and are so sluggish and indifferent in their respective offices that the artful and active scoundrel is allowed to parade the Country without interruption, and commit all imaginable mischief. . . .”. “What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the province! Most of the people have lost all confidence – I however speak loud and look big. . . .”. (Dictionary of Canadian Biography)

The citizens were apathetic because they thought that becoming part of America was inevitable.

Who Won The War Anyway?

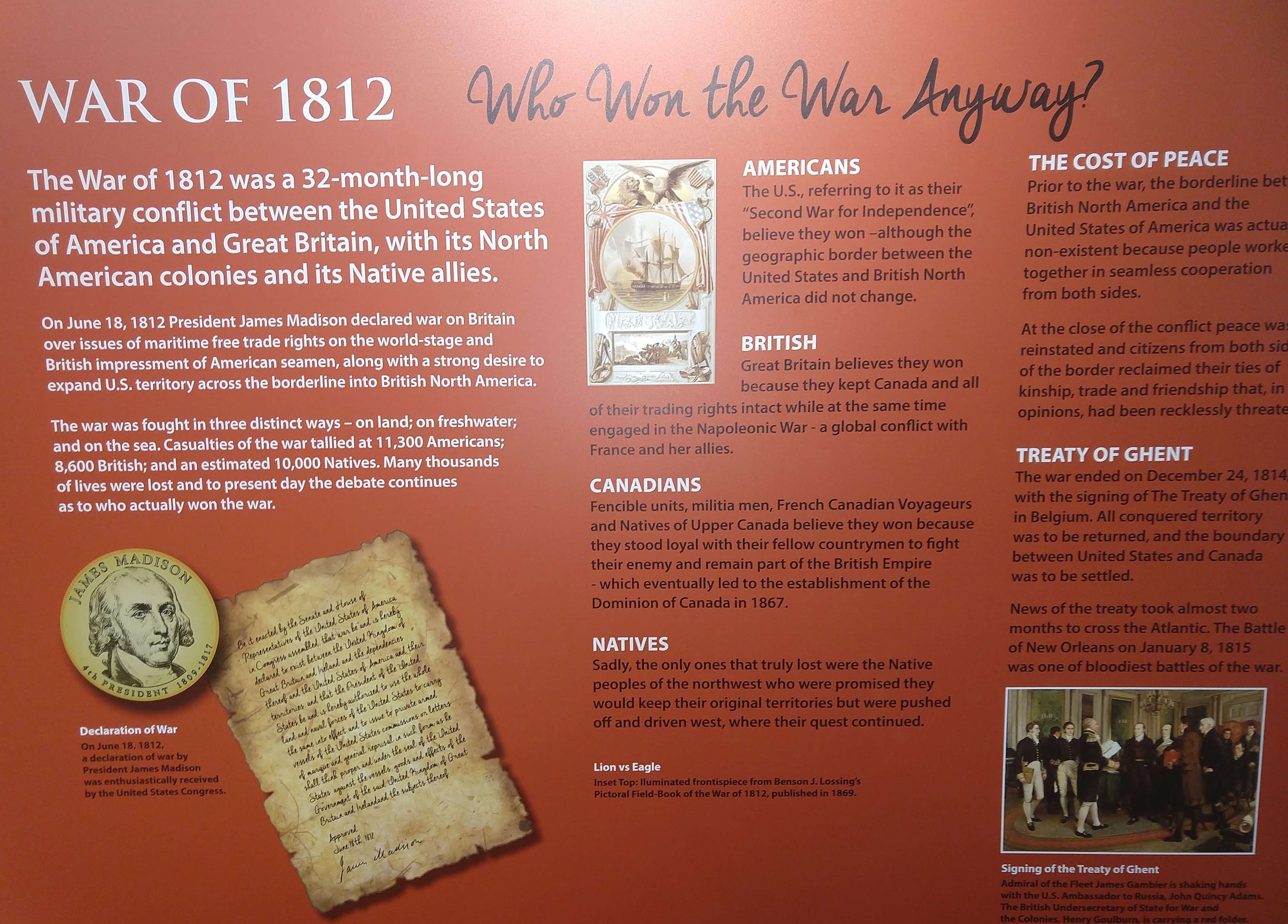

This plaque notes that the War of 1812 was a 32-month long military conflict between the United States of America and Great Britain, with its North American colonies and its Native allies. On June 18 1812, President Madison declared war on Britain over issues of maritime free trade rights on the world’s stage and British impressment of American seamen, along with a strong desire to expand US territory across the borderline into British North America.

The war was fought in three distinct ways – on land; on freshwater and on the sea. Casualties of war tallied at: 11,300 Americans; 8,600 British; and an estimated 10,000 Natives. Many thousands of lives were lost and to present day the debate continues about who actually won the war.

Note the picture of a coin with James Madison’s image on it and a copy of the Declaration of War in the above photo.

THE AMERICANS -They referred to this was as their ‘Second War for Independence’. They believed they won even though the geographic border between the United States and British North America did not change.

THE BRITISH – They thought they won because they kept Canada and all of their trading rights intact even though they were engaged in the global confilct with France and its allies – the Napoleonic wars.

THE CANADIANS – Fencible units, militia men, French Canadian Voyageurs and Natives of Upper Canada believe they won because they stood loyal with their fellow countrymen to fight their enemy and remain part of the British Empire – which eventually led to the establishment of the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

THE NATIVES – Sadly, the only ones that truly lost were the Native peoples of the northwest who were promised they would keep their original territories but were pushed off and driven west where their quest continued.

THE COST OF PEACE – Prior to the war, the borderline between the United States of America and British North America was actually non-existant because people worked together in seamless cooperation from both sides. At the close of the conflict, peace was reinstated and citizens from both sides of the border reclaimed their ties of kinship, trade and friendship that in their opinion, had been recklessly threatened.

The war ended on December 24 1814, with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent in Belgium. All conquered territory was to be returned, and the border between United States and Canada was to be settled.

News of the treaty took almost 2 months to cross the Atlantic. The Battle of New Orleans on January 8th 1815 was one of the bloodiest battle of the war.

As early as 1807, relations between the Americans and the British were growing strained due to conflicting foreign and trade policies of the two countries, notably over the control over the Great Lakes and Fur Trade routes. When the United States declared war on Great Britain in June of 1812, nearby Fort St. Joseph became a rallying point.

The Fort’s garrison commander Captain Charles Roberts, knew they were vulnerable and decided that his best defence was a good offence. On July 17, leading a force of about 40 regular soldiers, 150 Canadians and over 300 Ojibway, Roberts captured the American fort of Mackinac Island therefore serving notice to the American garrison that war had been officially declared.

Charles Ermatinger was a key contributor in this battle as he not only led 50 of his own men in the siege, but had a familiarity with the region which Roberts acknowledged to have been of great value.

Commended For Bravery: In a letter to General Isaac Brock from Charles Roberts dated July 17 1812, Ermatinger was commended for his bravery. The letter said, ‘ Sir… I took immediate possession of the Fort and displayed the British colours. The Indians, although these people’s minds were much heated (once) the Capitulation was signed they all returned to their canoes and not one drop whither of man’s nor animal’s blood was spilt… I cannot conclude this letter without expressing my warmest thanks to my own officers, to the Gentlemen of St. Joseph and of St. Mary’s.

“Captain Roberts, a valiant officer, arranged that an attack should be made on Fort Michilimackinac. The assistants were divided into three companies and the officers commanding were… John Johnston, Charles Oakes Ermatinger, and J.B. Nolin. The expectation succeeded and the British flag was soon floating over the fort – then called ‘The Gibraltar of the Lakes.’ “

Common understanding and strong friendships helped Europeans and Natives create mutually beneficial fur trading partnerships. Alliances based on kinship and reciprocity were important and involved exchanges such as, ‘I give to you that you might give to me’. Rituals such as marriages often sealed committments.

Men from the key fur trading companies would marry the daughter of an influential Native chief or a famous Native hunter. This guaranteed success through establishment of a tribal connection in many ways; it provided an unending source of raw resources; protection from competition; guides; and interpreters of Native language and customs.

Some traders left their Native women and children behind when they moved on to a new post. but made sure they were provided for by others. This process was called ‘turning off’ – a phrase that is said to come from a formal waltz step. Few traders, unlike Charles Ermatinger, took their wife and family with them when they moved and married in a Christian ceremony.

Marrying For Power: Charles Oakes Ermatinger launched his fur trade career in 1797 in the Sandy Lake area near the headwaters of the Mississippi River. Here, he secured his future by marrying Mananowe (Charlotte) the Ojibway daughter of Katawabeda or Breche (French), Broken Tooth (English) an influential policy chief of the Sandy Lake tribe.

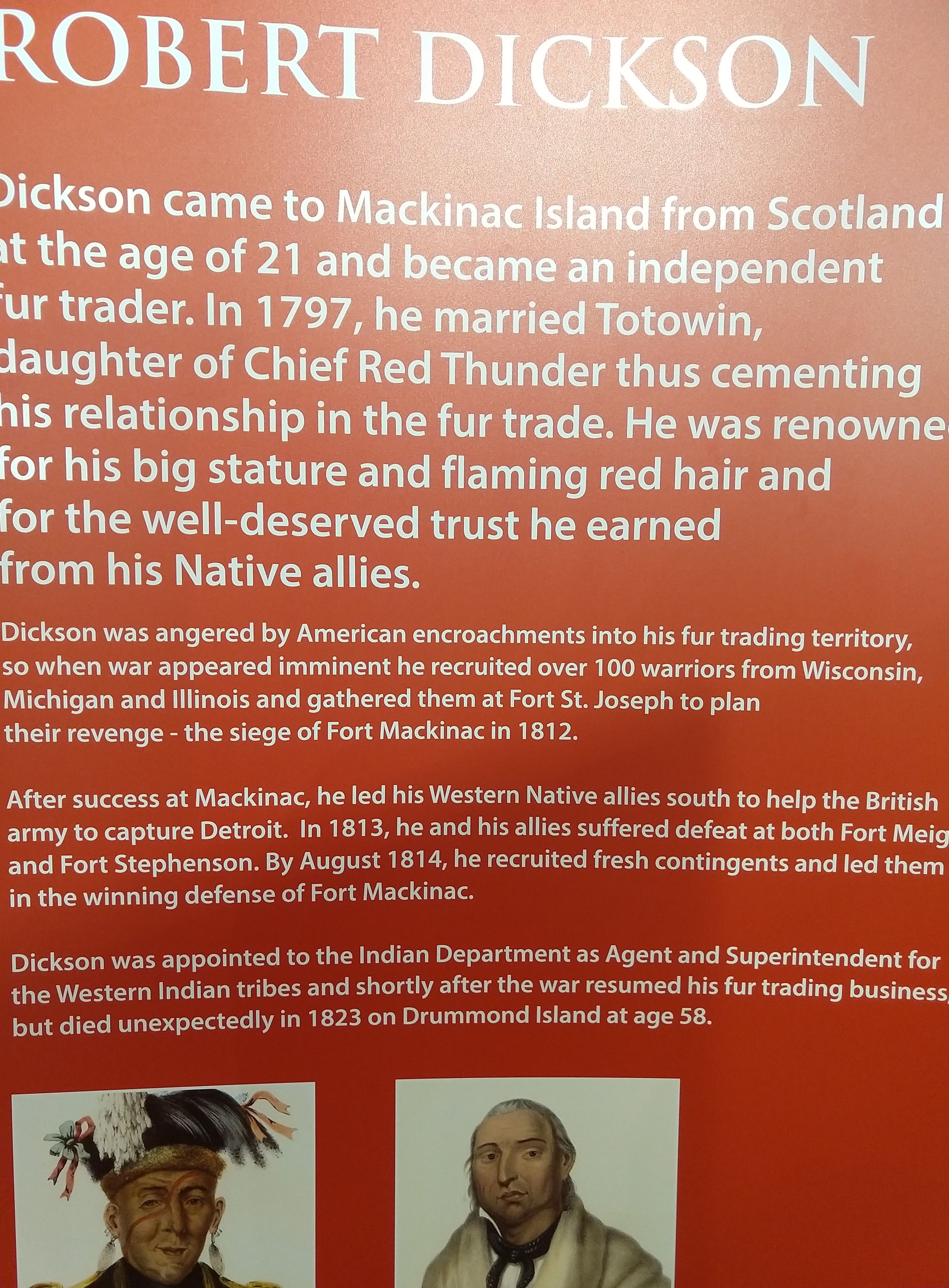

Robert Dickson

Dickson came to Mackinac Island from Scotland at the age of 21 and became an independent fur trader. In 1797, he married Totowin, daughter of Chief Red Thunder thus cementing his relationship in the fur trade. He was renowned for his big strature and flaming red hair and for the well-deserved trust he earned from his Native allies.

Dickson was angered by American encroachment into his fur trading territory so when war appeared imminent he recruited over 100 warriors from Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois and gathered them at Fort St. Joseph to plan their revenge – the siege of Fort Mackinac in 1812.

After success at Mackinac he led his Western Native allies south to help the British army to capture Detroit. In 1813, both he and his allies suffered defeat at both Fort Meighn and Fort Stephenson. By August 1814 he recruited fresh contingents and led them in the winning defense of Fort Mackinac.

Dickson was appointed to the Indian Department as agent and Superintendent for the Western Indian tribes and shortly after the war resumed his fur trading business but died unexpectedly in 1823 on Drummond Island at age 58.

Before the war began, Brock sent Dickson an urgent message asking for help with recruitment of Natives. Dickson sent his reply with his two most trusted friends, Wabasha and Little Crow. By early July 1812, a force of over 600 Dakota warriors were ready to fight alongside the British. The Dakota called the War of 1812 Pahinshashawacikiya or ‘When the Red Head Begged for Our Help’

From Dickson’s speech to the Dakotas:

“… these faithless people they must be told in a Voice of Thunder that the object of the war is to secure to the Indian Nations the boundaries of their territories… come then my Red Children and join yourselves to me and my White Children and let us fight them together until they shall ask for peace.

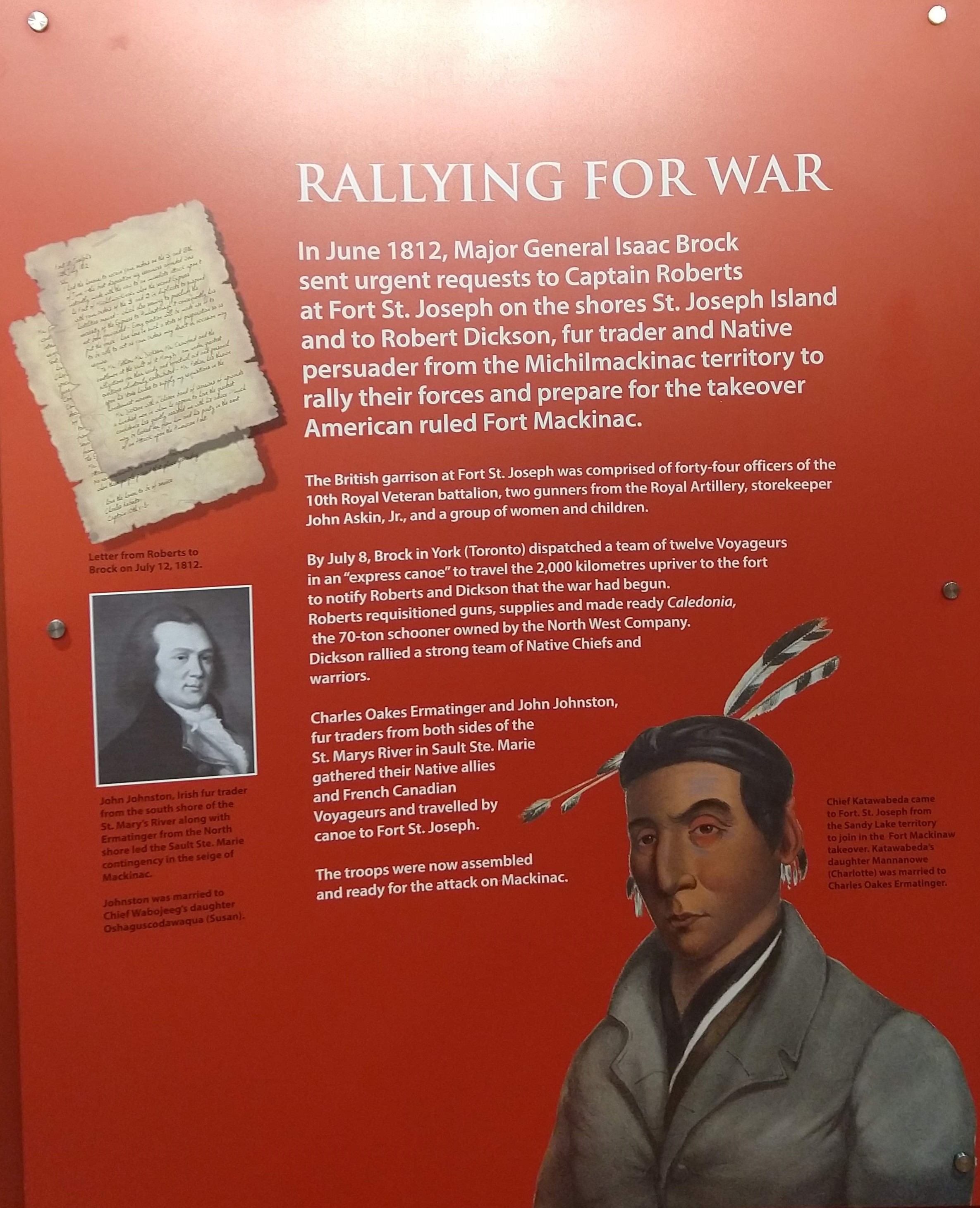

In June 1812, Major General Isaac Brock sent urgent requests to Captain Roberts at Fort St. Joseph on the shores of St. Joseph Island and to Robert Dixon, fur trader and Native persuader from the Michilimackinac territory to rally their forces and prepare for the takeover of American-ruled Fort Mackinac.

The British garrison at Fort St. Joseph was comprised of 44 officers of the 10th Royal Veteran Batallion, two gunners from the Royal Artillery, storekeeper John Askin Jr., and a group of women and children.

By July 8, Brock in York (Toronto) dispatched a team of 12 Voyageurs in an express canoe, to travel the 2,000 kilometres upriver to the fort to notify Roberts and Dixon that the War had begun.

Roberts requisitioned guns, supplies and made ready Caledonia – the 70 ton schooner owned by the North West Company. Dixon rallied a strong team of Native Chiefs and Warriors.

Charles Oakes Ermatinger and John Johnston, fur traders on both sides of the St. Mary’s River in Sault Ste. Marie gathered their Native allies and French Canadian Voyageurs and travelled by canoe to Fort St Joseph. The troops were now assembled and ready for the attack on Mackinac.

Inset Photos: Chief Katawabeda came to Fort St. Joseph from the Sandy Lake territory to join in the Fort Mackinac takeover. Katawebeda’s daughter – Mananowe (Charlotte) was married to Charles Oakes Ermatinger.

John Johnston, Irish fur trader from the south shore of the St. Mary’s River along with Ermatinger from the north shore, led the Sault Ste Marie contingency in the siege of Mackinac. Johnston was married to Chief Wabojeeg’s daughter – Oshaguscodawaqua (Susan).

Lieutenant Porter Hanks – 1st Prisoner of War

Lieutenant Hanks, commander of Fort Mackinac, was one of the first prisoners taken in the War of 1812.

Perched on an island in the strait which connected Lake Huron with Lake Michigan, the fort was a strategic target At this remote outpost Lt. Hanks had no idea that the war had begun when on July 17, a force of more than 500 British soldiers and Native allies descended from the hills around the fort and demanded its surrender. Hanks had but 2 choices: annihilation or capitulation. Not surprisingly he chose the latter and became a prisoner.

Hanks, only 24 years old, was paroled back to the United States with the stipulation he not fight again. He was held at Fort Detroit where he was facing a court martial for his surrender of Mackinac. While waiting there for a military tribunal to convene, the British forces under General Isaac Brock attacked the fort. A cannonball ripped through the room where Hanks was standing cutting him in half and killing the officer next to him as well.

Captain Charles Roberts

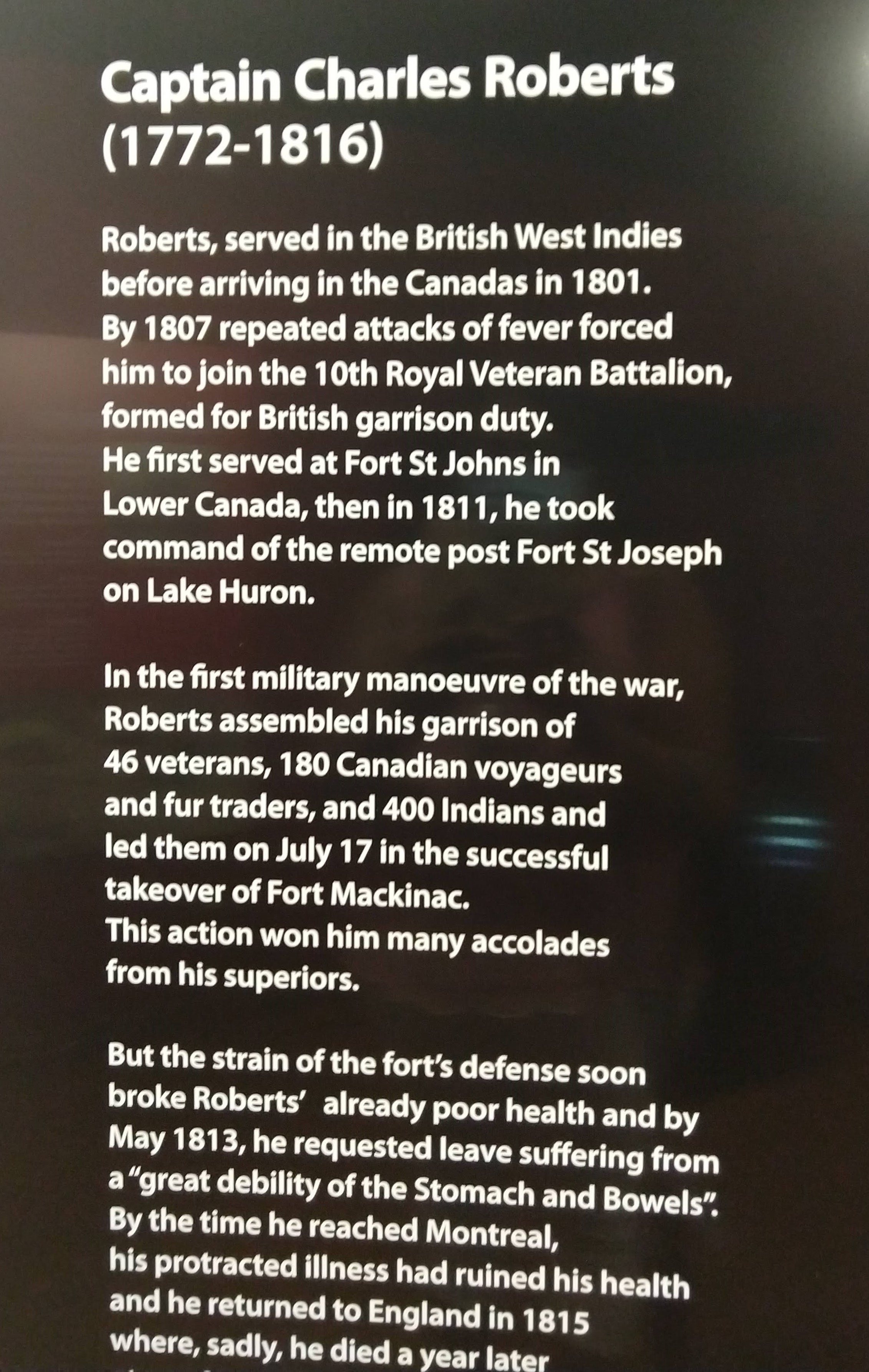

Roberts served in the British West Indies before arriving in the Canadas in 1801. By 1807, repeated attacks of fever forced him to join the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion formed for British garrison duty. He first served at Fort St. Johns in Lower Canada, then in 1811, he took command of the remote post Fort St. Joseph on Lake Huron.

In the first military manoeuvre of the war, Roberts assembled his garrison of 46 veterans, 180 Canadian Voyageurs and fur traders, and 400 Indians and led them on July 17 in the successful takeover of Fort Mackinac. This action won him amny accolades from his superiors.

But the strain of the fort’s defense soon broke Roberts’ already poor health and by May 1813, he requested leave suffering from a ‘great debility of the stomach and bowels’. By the time he reached Montreal his protracted illness had ruined his health and he returned to England in 1815, where, sadly, he died a year later.

The historical record from this article is very telling. One of the take-aways I get from this information (which is all new to me because I never examined the photos I took), is the debt of gratitude Canada owes to the valiant Native community and their fur trading allies. Without their help, Canada would not be a nation, but another few states of the United States of America.

Author’s Note: Lynette is the owner of ChristianRoots Canada. Blogger. Publisher. Course Creator. Passionate about Canadian History from the perspective of God’s Providence.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of