Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

Home / John Graves Simcoe – Toronto Day

Toronto celebrates Simcoe Day on the first Monday in August in honour of John Graves Simcoe. But who was John Graves Simcoe?

Simcoe was a British Army Lieutenant Colonel, the first Lieutenant-General of Upper Canada (somewhat like a Premier’s role) from 1791 until 1796. He was a visionary, a politician and a devout Anglican who laid the infrastructure of settlement in Ontario by building roads in an intentional, strategic manner. He had served in the British army during the American War of Independence (1776/1783). That experience coloured his perspective on republicanism compared to conservatism. He saw his role as developing Upper Canada as a model English society built on conservative British principles which were superior to the republicanism of the United States.

During the war In 1777, he was unsuccessful in forming a Loyalist Regiment of Free Blacks from Boston. Soon afterward, he was appointed the commander of the Queen’s Rangers instead. The Queen’s Rangers was a well-trained light infantry of over 300 men. He participated in other battles until December of 1781 at which time he was invalided back to England where he convalesced at the home of his godfather Admiral Samuel Graves, whose name he bore.

Simcoe’s father, John Simcoe, was the ship’s captain on James Cook’s ship, HMS Pembroke, from 1757 to 1759. John Simcoe was a close friend of Admiral Samuel Graves, who became the godfather to John Graves Simcoe. John Simcoe died of pneumonia on Anticosti Island at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in 1759. His ship was making its way to Quebec after participating in the siege of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.

At the time of his father’s death, John Graves Simcoe was about 7 years old. Shortly after, his mother died leaving him an orphan. He was then raised by Admiral Samuel Graves. It is said that his father left a list of maxims for his education, which he referred to often. These included:

In 1782 besides being promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, he also married Admiral Graves’ niece – Elizabeth Gwillim, whom he met while convalescing at the Admiral’s home. She was an accomplished artist who painted many landscapes of Upper Canada. In 1791, Simcoe was appointed as Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada.

Before 1791, all of Upper and Lower Canada (previously New France) was called the Province of Quebec. During and after the War of American Independence (1775 – 1783) there was an influx of immigrants from America who were loyal to Britain (Loyalists) fleeing North to Britain’s colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and the Province of Quebec. Many were given land, chiefly in what is now Southern Ontario.

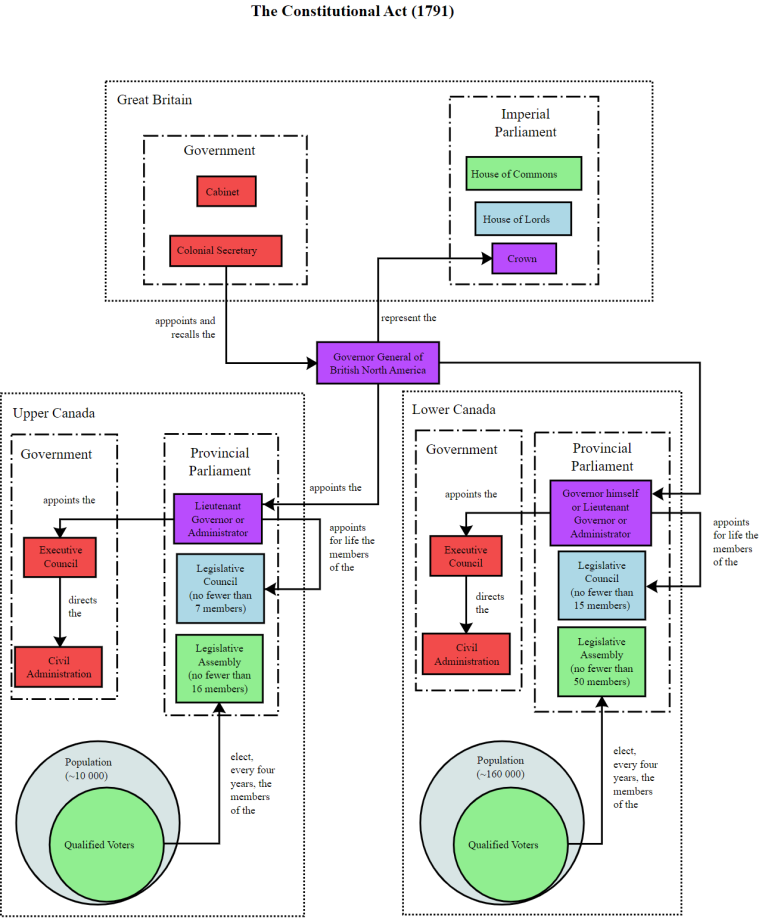

In 1791, the Constitution Act divided the Province of Quebec into two. The largely unpopulated western part of the Province was called ‘Upper Canada’ with mostly English-speaking loyalists, and the eastern part became Lower Canada, which were mostly French-speaking.

Both Upper and Lower Canada were now governed by their own Legislative Council (appointed like the Senate) and Legislative Assembly (elected like the House of Commons), with the Governor General representing the British monarch.

John Graves Simcoe was appointed as the first Lieutenant Governor (Administrator) of Upper Canada and initially lived in Newark ( Niagara on the Lake).

Simcoe, like many men loyal to Britain, held to the hope that after the Revolution, Americans will be largely disappointed with republicanism and migrate to Upper Canada. This did not happen. He desired to build a Canada which functioned with the British constitutional model, but with an economic engine fashioned after American capitalism.

Simcoe thought that it might be easy to encourage American immigration to the southwestern peninsula of Upper Canada so that Canada could control the commerce of the American west. He was excited by the dream of Upper Canada becoming economically important to the continent and the empire at the time. If only he was alive today he would see how important trade has become between Ontario, the rest of the continent and the world.

In his mind, a land-granting system which was administered efficiently and fairly would be attractive to immigrants and foster loyalty to the British Government and to their new country. As with all visionaries, there were areas of disconnect between theory and practice. As a result, the actual administration of land grants had mixed success. He had planned to borrow the road-building methods of the Romans…

The army would set up winter quarters where the town was to be situated. Trees would be felled and the proposed settlement cleared, roads would be built, and the anticipated settlers would have a detachment of soldiers living among them for protection. This would boost trade since the soldiers would provide a ready market for goods and services developed by the settlers.

The soldiers in this case would be the Queen’s Rangers who would form the nuclei of a cohesive settlement, and as new immigrants settled around them, they would all magically blend into loyal British subjects.

Simcoe, the visionary, requested twelve companies of soldiers but got only two. In spite of the smallness of their unit, the Queen’s Rangers were a very important part of Simcoe’s road-building legacy. From their employment in June 1796 until they were disbanded in 1802, they were the road builders of Upper Canada.

Simcoe encountered other issues because his idealism got the better of him. For example, the Constitutional Act of 1791 allocated 1/7 th of the total land mass of upper and lower Canada as clergy reserves. This was specifically to help the Anglican Church to gain from the sale or lease of these lands. Allocation of crown lands and clergy reserves in each township plus the zoning regulations in towns, made land grants complicated.

Another problem arose when he, in good faith, granted entire townships to individuals who were supposed to organize settlers. These organizers were to become the British equivalent of the new local ‘gentry’. This had a corrupting effect on his good intentions for many years as recipients took advantage of their generous land allotments. The majority of the grants were over 500 acres in the prime location of ‘the Home District’ (York Township and the Western District) where the most effort was expended at settlement. These went to favourites holding government offices. This number and size of allotments grew annually but was not abandoned.

Previously, in 1788, shortly after the American War, land boards had been set up to facilitate the orderly settlement of loyalists but they were slow in land allocation. In the short term, the regulations to screen out speculation did not work and in the long term there was confusion and delay in issuing legal titles.

Impatiently, Simcoe sped up the process of land allocation by ordering large grants where the title was not clear, which he then used to attract settlements to specific areas. One such grant was given to William Berczy whose settlers built part of Yonge Street and settled in Richmond Hill. Read the article here.

He abolished the land boards in 1794, which did not really help the situation because it destroyed the process of screening applicants. In spite of it all, he achieved the goal of making Upper Canada a place where access to land acquisition was easy for settlers. He basically had to accept settlements as they came as opposed to the grand plan he had devised in true visionary fashion while still in England.

As a result, whatever settlement policies were utilized, they determined the course of the development of Upper Canada for generations. For himself, his military rank allowed him 5,000 acres. He judiciously spread his allocation in 1,000 acre parcels in York and Western Ontario where his government focused its settlement efforts.

In true visionary fashion, immediate problems did not excite him like long-range planning did. He thought that laying the foundations for the future of Canada was his most important function regardless of the speed of the results. This was borne out in his road-building projects. He did not construct roads for the convenience of the established settlers. He thought that the responsibility for those roads should be left to the local authorities. Instead, he built roads which were strategic for communications and for future development of other settlements.

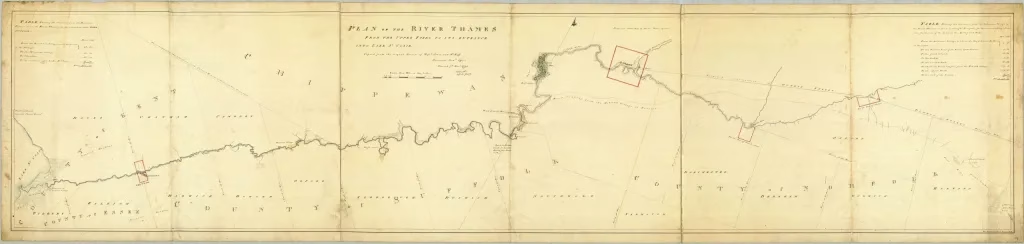

In May 1793, the first road on which the Queen’s Rangers began work was Dundas Street. It ran from Burlington Bay (probably from the current Highway #6) north to what is currently Clappison’s Corner, and east through Waterdown, Oakville, Mississauga, Etobicoke, Islington, and into Toronto.

Because of Simcoe’s focus on strategic communications and the development of future settlements, Simcoe’s original design was a road which began at the head of navigation (Burlington Bay) to the future centre of the province (Toronto). At that time, it ran ‘from nowhere to nowhere’, though there was no settlement there as yet, and ended at the valley of the river he renamed the ‘Thames’. This was probably the Humber River. Two years later (1795) the road was extended east to York.

When Simcoe began to lay out the town of York, his vision was that it would become a garrison, an arsenal and a naval base. However, Kingston became all those things because of its previous history. Simcoe did not quite accept American independence and unity as a fact. He continued to think of the Americans only as a political threat (Toryism vs Republicanism). He did not see them as a military threat.

In 1791 when Simcoe arrived in Upper Canada, British garrisons still occupied border posts on the American side. Both the British and the Iroquois Confederacy still held out hope for a Native ‘buffer’ state as compensation for the loss of Iroquois lands in upstate New York during the American Revolution (1774 – 1785).

By September 1794, it was thought that there would be an American invasion. The Queen’s Rangers assembled in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake in preparation for the attack. Simcoe’s family was whisked away to Quebec by John McGill.

Simcoe realized the need for a Naval force on Lake Ontario and a garrison in Upper Canada which was large enough to defend both Upper and Lower Canada. Simcoe saw the control of Lake Ontario East of York as a key focus of strategic communications resulting in the reorganization of the Provincial Marine instead of road development. After Simcoe left Canada, and not until 1799 with the building of the Danforth Road, did Simcoe’s system inevitably point to York (Toronto) as the centre of the province.

Again, in keeping with his vision of strategic communications and the future development of other settlements, in February 1796, the Rangers finally extended Yonge Street to the Holland River to provide strategic access to the Great Lakes. Berczy had completed the building of the southern half of Yonge Street. Settlement was promoted along this road that offered security PLUS access from Lake Ontario to the upper Great Lakes. Simcoe’s focus was on York and the Western part of the province.

Even though he did not give as much focus on the other loyalist settlements which stretched from Kingston eastwards to Cornwall. He accomplished in four years, with less technology than is available in 2023, feats of settlement in southern Ontario, that which takes many more years to accomplish.

Continued in Part 2

Author’s Note: Lynette is the owner of ChristianRoots Canada. Blogger. Publisher. Course Creator. Passionate about Canadian History from the perspective of God’s Providence.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of