Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

Home / John Graves Simcoe – Toronto Day (2)

John Graves Simcoe became a politician when he was first elected to the British House of Commons for the Cornish borough of Mawes in 1790. His recorded contributions to the speeches in the Britain’s House of Commons include a speech about the new constitution of Quebec and most likely a motion to abolish the slave trade.

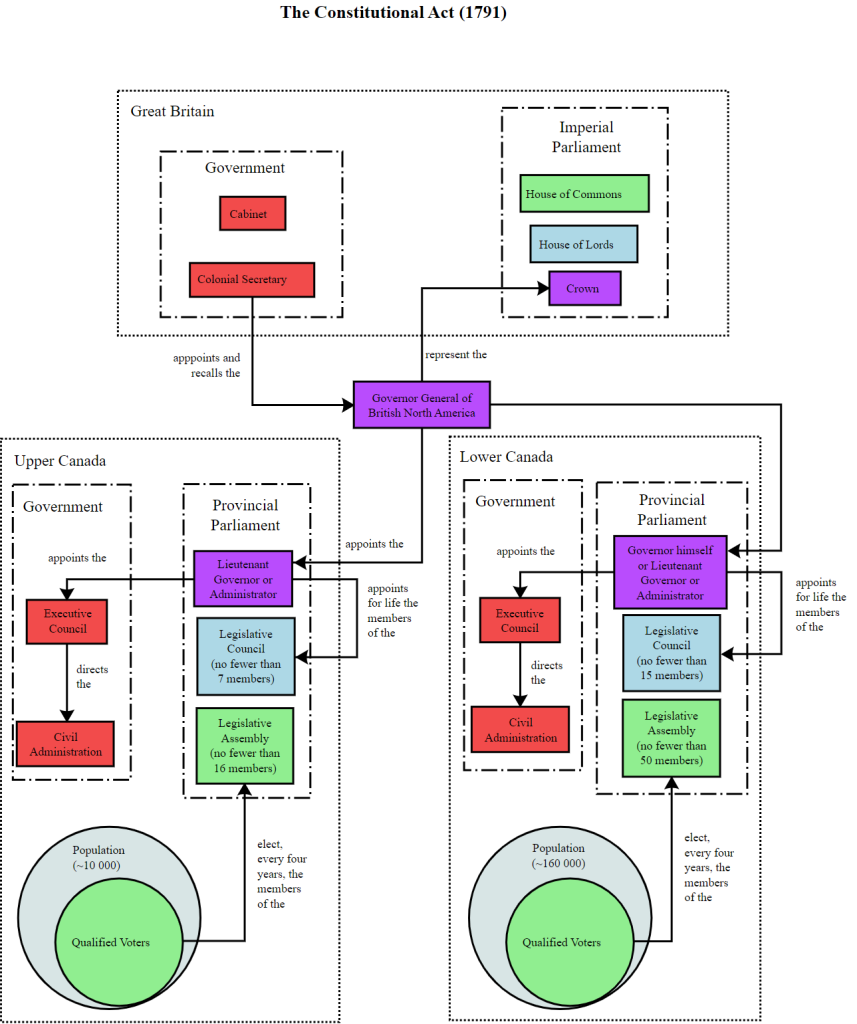

In 1791, Simcoe was appointed Lieutenant General of the new Loyalist province of Upper Canada at the same time that Sir Guy Carleton was appointed to Lower Canada as Lieutenant Governor and Governor General of both provinces.

Sir Guy Carleton was an army officer and served as Governor General twice in Canada – Between 1776 and 1795, he served as the Governor of the Province of Quebec and the Governor General of British North America.

Guy Carleton came from a Protestant military family in Ulster. His father died when he was aged 14 and his mother remarried Reverend Thomas Skelton three years later (1742). Three years later (1745) he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant.

As a lieutenant, he became the friend of James Wolfe who became a major-general in December 1758. Wolfe led his army in the famous conquest of Quebec City. Carleton was appointed as his quarter-master, responsible for supervising the stores and distributing supplies. He was also given responsibility as an engineer who supervising the placement of cannons. He was injured in 1759 in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

In 1775, he commanded British troops in defending Quebec against the rebels in the American Revolutionary War and in 1776, a counteroffensive that drove the enemy from Quebec. In 1782/1783, he was commander in chief of all of Britain’s forces in North America. He ensured that Britain’s promise of freedom for slaves who joined the British forces was kept. In that respect, he appointed Samuel Birch to create The Book of Negroes to keep proper records. In 1783, he oversaw the evacuation of British forces, Loyalists and over 3,000 freedmen from New York City to the British Colonies of the north.

Simcoe was so zealous to inaugurate his new government that he spent 18 months in preparation for the position. His grand plan was to see rapid economic growth, and to that end he developed ambitious and what was categorized as ‘unrealistically expensive’ plans. These included constitutional, religious and educational development of his new province. Even before he had seen the province he envisioned making Upper Canada a ‘model of England overseas’. His first speech to the legislature in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) was made in September 1792.

Because of his participation in the American War of Independence, Simcoe had a special interest in seeing the continuation of British conservatism, its institutions and its rule in North America. He had kept in touch with some of the Loyalist exiles and was genuinely sympathetic towards them. He had very little success in persuading the imperial administration to support his ambitious plans. In that vein,

However, even though Simcoe was disappointed with the level of education and the social status of the members of the Legislative Assembly, they were generally on the same page with the same goals in mind. His main job was to establish a constitutional framework of civil government in the new province. Settlers were not particularly interested in the details of setting up that system.

Most of the legislation he brought before them in the first session was not particularly controversial and included:

Two pieces of legislation were rejected. One for a land tax and the other for education. Two pieces of legislation were initiated by the assembly – the legalization of marriages performed by magistrates and town elections. He conceded to the marriage issue with the caveat that if there were five Anglican clergymen in the district with one of them within eighteen miles, the bill was null and void.

One area of compromise in May 1793 was settling for a gradual rather than an immediate abolition of slavery in the province. In 1794, the assembly accepted the formation of a Superior Court or ‘Court of King’s Bench’ as it was called.

A bill of 1793 affirmed that the election of township officers can only happen under the control of justices of the peace who were appointed by the Lieutenant Governor and remained the real power of local government.

Dealing with the Legislative Council was more difficult. He did not trust merchants and land speculators. There were less than 10 councilors with never all of them present together, so direct confrontation and defensiveness worked against him.

Special interest rivalry was palpable. In theory, he expected their independent judgment of his agenda but in practice he was disappointed that they did not just ‘rubber-stamp’ his projects and agendas. Areas where he had common ground with his two most outspoken critics were:

John Graves Simcoe was inexperienced as an administrator and had not had years of political experience as master of manipulation and compromise. However, the assembly and the Council found him to be accessible, frank and reasonable. They found him warm, sympathetic and loyal to his subordinates.

If only Simcoe’s father were alive to see his son’s accomplishments in the wilderness of Upper Canada, he would have seen the roads he mapped out and built for cities of the future (Toronto, Kingston, Burlington, Hamilton Niagara on the Lake etc), the foundations of the Parliamentary system of democracy he laid down, and the accolades of those who knew him best.

He lived out his father’s maxims for his life:

John Graves Simcoe left Canada never to return. But the system of roads dictating settlements and not the other way around, was responsible for the planned settlements of areas like Niagara on the Lake, London, Burlington, Hamilton, York and eventually Kingston.

Upper Canada (Ontario) and York (Toronto) have much for which to thank John Graves Simcoe.

Author’s Note: Lynette is the owner of ChristianRoots Canada. Blogger. Publisher. Course Creator. Passionate about Canadian History from the perspective of God’s Providence.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of