Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

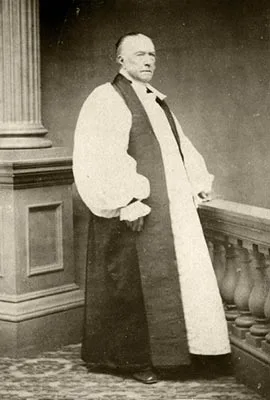

Home / John Strachan – Training The Next Generation

It is often said that Eggerton Ryerson (1803-1882) is the father of public education in Ontario and Canada. However, on doing research about the Protestants who shared a vision to raise the next generation of Canadians to ‘glorify God and enjoy him forever’, one is brought face to face with the reality that Ryerson in fact, was walking in the footsteps of other giants.

Two giants of note are John Strachan who lived from 1778 to 1867, and Sir John William Dawson who lived from 1820-1893. John Strachan trained and mentored a cohort of young men who became administrators, lawyers and businessmen of Upper Canada when it was a brand new British colony.

Sir William Dawson, a contemporary of Ryerson, is called the Father of Paleontology because of the extensive research he engaged in, in the study of the fossil record. He was also a contemporary of Charles Darwin and was God’s servant sent to refute Darwin’s lies. He was responsible for making McGill University the world-class university it became because of his passion for truth and Science.

Strachan’s parents were well-off but not rich. He was the youngest of 6 children and his mother’s favourite. She decided his vocation as a minister, because she believed that a liberal education would make him a ‘gentleman’. He attended St Andrews University as a part-time student where he took divinity classes and was befriended by Thomas Duncan, who became a professor, and Thomas Chalmers, who became the leader in the Free Church of Scotland secession movement in the 1840s.

In March 1799, he received an offer “to go to Upper Canada (Kingston) as a tutor to Richard Cartwright*s children, and the children of other important people in Kingston such as John Stuart* – clergyman of The Church of England” who, like Strachan, once belonged to the Presbyterian Church. He had accepted this job at an annual salary of £80 plus room and board from the Cartwrights. An unexpected blessing was that Strachan was able to continue his own education with Stuart’s assistance.

Richard Cartwright and John Stuart were loyalists from New York. Cartwright was well-read, a member of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada, and a well-connected merchant. Not long after, Strachan also became connected with important merchants in Montreal.

He arrived at Cartwright’s home on December 31st 1799. Four years later, in 1803, Cartwright was able to write Strachan a letter of reference to present to the Bishop of The Church of England, Bishop Jacob Mountain*, recommending that he ordained Strachan as a minister in the Church of England. The letter also indicated that Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Peter Hunter* intended to appoint Strachan to the mission at Cornwall.

On 22 May 1803 Bishop Mountain ordained him, first as a deacon, and a couple of weeks later in June, as a priest. By the Summer of 1803, Strachan began his new life at Cornwall. His reputation as an industrious, successful parish priest gave him recognition among clergymen in Upper and Lower Canada. His influence grew when he established ties by marriage, by the friendships he made, and by a reputation for being an amazing classroom teacher. Within a few weeks of his settling in Cornwall, Strachan was in touch with the parents of some of the boys whom he had been teaching in Kingston to suggest that they be sent to him to continue their schooling.

Among those who came were John* and William Macaulay*. John eventually rose to be influential in Kingston as a newspaper publisher. Another pupil was 12-year old John Beverley Robinson, whose father had died and was being raised in the home of John Stuart. He lived with Strachan for a while eventually becoming the Attorney General of Upper Canada.

Strachan had a remarkable influence on the minds of many young men. Beginning with 20 men in 1804, by 1812 he had a constant school of 40 pupils. His clientele came from the families of upper class businessmen, government and other professions. His intent was to shape their minds so that they would become the potential leaders of the next generation.

Being trained by Thomas Chalmers in Edinburgh probably helped him to be creative in developing his curriculum for Upper Canada. His school – The Cornwall Grammar School, provided an academic curriculum that was varied and of a high standard. He developed a Math textbook, and he emphasized teaching natural science to his pupils along with the classics. He even secured government funding for scientific equipment.

Instead of corporal punishment – the norm in those days, he developed competitiveness coupled with a system of rewards which both interested his pupils and challenged them to excellence. His ultimate goal of training these minds was:

He did not see the acquisition of knowledge as an end in itself. Daily prayers were a part of the school program and those boys belonging to the Church of England (the majority) were taught the church catechism. On Saturday mornings, students received a religious and moral lecture on which they were quizzed for the rest of the week. His hope was to raise influential leaders who would set a standard of social decorum for Upper Canada.

In 1807 The Grammar school Act was passed and his school began receiving government support.

In 1807 he married into the McGill family by marrying the widow, Ann Wood McGill, the sister-in-law of James McGill of Montreal. Her deceased husband, Andrew, was a Cornwall physician. To Strachan, marrying well, building a good church, parsonage, and school was not enough. He needed the validation of a degree to increase his influence. The University of Aberdeen, through the request of a Dr. Brown, conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity.

His ambition to found a university took root in conversations with James McGill who wondered aloud to Strachan how he should dispose of his extensive property and wealth, having no family of his own. Strachan suggested leaving it to further the cause of education. As a result, McGill appointed Strachan as one of four trustees to manage the bulk of his estate. They were to turn it over to the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning to establish a college IF a college was established within 10 years of his death. Strachan was not chosen as the Principal, but he was one of the founders of McGill University.

In 1811, his old friend and mentor John Stuart passed away. He had hoped to gain the bishopric of York in Stuart’s place but that went to Stuart’s son. However, General Isaac Brock, the administrator of the province, offered him a position at Kingston as the bishop’s commissary and rector at Kingston, plus the chaplaincy of the garrison and Legislative Council. Kingston was the provincial capital at the time. He and his family arrived in June of 1812, just as the US declared war on Britain and her North American provinces.

Strachan wielded enough influence that he was successful as an education lobbyist. He had been calling for the government to invest in a system of elementary education (Common Schools) and a provincial ‘Board of Education’ to supervise the system at every level. Strachan would devote much effort for the rest of his career to implement this.

In 1816 Strachan got his wish when Lieutenant Governor Gore endorsed his proposals and later that year the legislature passed a Common School Act, which apparently had been largely drafted by Strachan. There were only two amendments made in 1820 and 1824, but this act remained the basis of Upper Canada’s elementary school system until 1841.

In 1819 a revised Grammar School Act adopted some more of his suggestions, but fell short of providing free education. However, provision was made to give free education to ten poor students in each district. He was not able to influence the beginning of a university in Upper Canada.

Strachan arrived in Canada in 1799. Four years later (1803) he was a parish priest and school principal of The Cornwall Grammar School. Four years after that, he orchestrated the Grammar School Act. In 1816, he successfully orchestrated The Common School Act – the basis of Upper Canada’s elementary school system until 1841.

In three decades, virtually one generation, John Strachan laid the foundations of elementary education; encouraged the establishment of McGill University and was one of its four trustees; trained a newspaper publisher, an Attorney General and other leaders of Upper Canada.

Most of his students came from families of upper class businessmen, government and other professions. With further investigation, one would no doubt find that his vision to shape the minds of potential leaders of the next generation extended to higher education in McGill University. He died in the year of Confederation. It will be interesting to find out how many leaders of Confederation were influenced by his legacy. And WHAT a legacy that was.

Author’s Note: Lynette is the owner of ChristianRoots Canada. Blogger. Publisher. Course Creator. Passionate about Canadian History from the perspective of God’s Providence.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of