Canadian History With New Eyes: The Dark Ages?

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

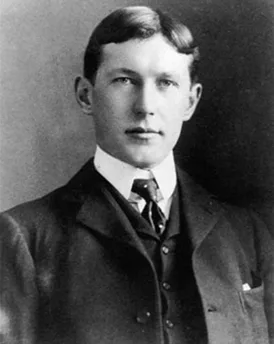

Home / The Life and Legacy of John McCrae: Soldier, Doctor, Poet

It is a terrible state of affairs, and I am going because I think every bachelor, especially if he has experience of war, ought to go. I am really rather afraid, but more afraid to stay at home with my conscience. — John McCrae

At 41, “Jack” McCrae could have justifiably remained in Canada and watched the unfolding drama of a world war from the safety of his home. Instead, he decided to serve on the Western Front.

Tragically, it would cost him his life.

John Alexander McCrae was born on November 30, 1872 in Guelph, Ontario.

His parents, David McCrae and Janet Eckford, were the children of immigrants and McCrae could trace his roots back to Scottish royalty. Raised Presbyterian, he would remain a devout Christian all his life. His friend and first biographer, Sir Andrew Macphail, would later describe him as an “indefatigable church-goer”.

David McCrae was a retired Lieutenant-Colonel, and so his son grew up accustomed to military life and practice. As a child McCrae drilled with a local corps; as a young man he served in the Boer War, where he attained the rank of major.

While serving in that war, McCrae met one of his heroes, famed author and poet Rudyard Kipling. He described the event:

We met the High Priest of it all, and I had a five minutes’ chat with him—Kipling I mean. He visited the camp. He looks like his pictures, and is very affable. He told me I spoke like a Winnipegger. He said we ought to “fine the men for drinking unboiled water. Don’t give them C.B.; it is no good. Fine them, or drive common sense into them. All Canadians have common sense.”

Interestingly enough, the catch-phrase ‘lest we forget’ came from Kipling’s poem “Recessional” (“Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,/ Lest we forget—lest we forget!”), who had adapted it from Deuteronomy 6:12 (“Then beware lest thou forget the Lord”).

It is interesting that these two men, who each had a significant impact on what is now Remembrance Day, would actually meet. But McCrae probably never thought at the time that he himself would one day be to his country what Kipling was to England.

Once the war was over, and he had returned to Canada, McCrae returned to the pursuit of one of his other passions: medicine. He finished his studies, completing his degree in pathology. He also tutored; among his students were two of Canada’s first female doctors.

McCrae’s path in medicine, in retrospect, is truly impressive. He studied under famed doctor Sir William Osler at Johns Hopkins University; worked as a professor at several Canadian universities; and co-authored A Text-book of Pathology for Students of Medicine. At the same time he also ran a private practice.

Though McCrae worked long, hard hours, he still had time to visit family and friends. Not only a favourite uncle to his sister’s children, he was also a socialite who had many connections in higher circles. And throughout this time, he was writing poetry, some of which he published in Canadian newspapers.

In 1910, McCrae was approached by then Governor-General Earl Grey with a request to join him as a physician on a journey round the country. While travelling with Grey in Prince Edward Island, McCrae had the chance to meet a young woman named Lucy Maud Montgomery, who had just published her book Anne of Green Gables.

Four years later, while sailing to England for a vacation, McCrae learned on ship that Britain, and by extension Canada, had declared war on Germany. It was August 1914, and World War I was about to explode.

Although older than the average enlister, McCrae offered his services anyway and was accepted into the Canadian Army as a physician. He returned to Canada to train in Valcartier, Quebec. After months of poorly organized training, he and the other Canadians were shipped to a camp in Salisbury Plains, England.

McCrae preferred to fight rather than bandage, and the long delays and poor management by superiors irritated the disciplined soldier in him to no end. When he finally arrived on the scene in Europe, it was 1915 and the Second Battle of Ypres was just beginning. McCrae served with both the artillery and the nearby Essex Farm Dressing Station.

This battle is one of the most infamous in Canadian history–not only was it the first action the Canadians saw in that particular war, it was also the first battle that chemical warfare was introduced. On April 22, 1915, Canadians and their neighbours, the French, peered out of the trenches to see billowing yellow clouds overhead: chlorine gas from the Germans opposite.

For eager new recruits who were there for glory and believed the war would be “over by Christmas”, the basic horror and inhumanity of the situation that greeted them in Ypres was a shock. McCrae described the dismal scene,

The general impression in my mind is of a nightmare. We have been in the most bitter of fights. For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds… And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.

But more devastating to McCrae than his hellish surroundings was the sudden, tragic death of a good friend and former student: 22 year old Lt. Alexis Helmer. Helmer, born in Quebec but raised in Ottawa, was on assignment when he was hit by a stray shell and died instantly on May 2, 1915.

“Heavy gunfire again this morning,” McCrae wrote later that day. ‘Lieut. H—— was killed at the guns. His diary’s last words were, ‘It has quieted a little and I shall try to get a good sleep.’ His girl’s picture had a hole through it, and we buried it with him…I said the Committal Service over him, as well as I could from memory. A soldier’s death!”

With no chaplain available, McCrae recited, from memory, portions of The Book of Common Prayer over his friend’s grave. Although a small marker – a wooden cross – was erected, Helmer’s grave was soon lost and today it is unknown where he lies.

This incident impacted McCrae profoundly. In his grief he turned to something that had always been a solace for him: writing.

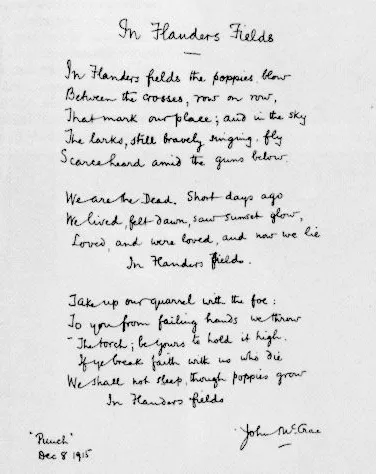

The day after his friend died, he penned these words in a little notebook:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place: and in the sky

The larks still bravely singing fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead: Short days ago,

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved: and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe

To you, from failing hands, we throw

The torch: be yours to hold it high

If ye break faith with us who die,

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

“A small group gathered together and John McCrae [recited] part of the burial service, which we all are familiar with: ‘I am the resurrection, and the life.’ John McCrae was terribly moved. Alex Helmer had been one of his close friends. Shortly after that, he went and sat on the ambulance, looking at the grave and then writing the original version of In Flanders Fields,” recalled Sgt.-Maj. Cyril Allison, a fellow officer who was with McCrae at the time.

“The poem was exactly an exact description of the scene in front of us both. He used the word blow in that line because the poppies actually were being blown that morning by a gentle east wind. It never occurred to me at that time that it would ever be published. It seemed to me just an exact description of the scene.”

What McCrae did next with this poem, which he titled “In Flanders Fields”, however, remains a mystery to this day. Some historians believe that McCrae, pleased with how it had turned out, sent it in to The Spectator, a British magazine, and then returned to his work.

Another story goes that McCrae wrote the poem, then crumpled it up and threw it out. But a friend retrieved it and mailed it to The Spectator.

Either way, the poem made it to The Spectator within a few months of Helmer’s death and was promptly rejected. However, a journalist discovered it and had it sent to Punch, another British magazine.

The poem was accepted and published anonymously in December 1915, and for the first time in history, “In Flanders Fields” was in print.

To use today’s terms, the poem literally went viral. It was, as The Canadian Encyclopedia puts it, “being memorized, copied into letters, set to music and translated into multiple languages. The poem was also used to raise $400 million for the war effort.”

“In Flanders Fields” had become the most famous poem of The Great War.

Macphail asserts in his work, John McCrae: An Essay in Character:

It is little wonder then that “In Flanders Fields” has become the poem of the army. The soldiers have learned it with their hearts, which is quite a different thing from committing it to memory. It circulates, as a song should circulate, by the living word of mouth, not by printed characters. That is the true test of poetry—its insistence on making itself learnt by heart.

After Ypres, McCrae, now one of the most famous Canadians alive, was transferred to the Canadian Army Medical Corps and promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel. He was extremely displeased with this arrangement – according to Allinson, he preferred to stay with his “beloved guns”.

Despite his reluctance, McCrae was soon placed in charge of a new hospital in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France: the No. 3 (McGill) Canadian General Hospital. He remained there until 1918.

McCrae’s friends soon noticed he had changed – the once youthful, energetic man was now growing old, tired, and cynical. He began using a cane.

The brutality and utter depravity of the sights McCrae witnessed daily on the battlefields were taking their toll.

Macphail describes these changes:

There are men who pass through such scenes unmoved. If they have eyes, they do not see; and ears, they do not hear. But John McCrae was profoundly moved, and bore in his body until the end the signs of his experience…A Nursing Sister in the American Ambulance at Neuilly-sur-Seine met him in the wards. Although she had known him for fifteen years she did not recognize him,—he appeared to her so old, so worn, his face lined and ashen grey in colour, his expression dull, his action slow and heavy.

To those who [had] never seen John McCrae since he left Canada this change in his appearance will seem incredible…Although he was upwards of forty years of age when he left Canada he had always retained an appearance of extreme youthfulness. He frequented the company of men much younger than himself, and their youth was imputed to him. His frame was tall and well knit, and he showed alertness in every move. He would arise from the chair with every muscle in action, and walk forth as if he were about to dance.

In 1917, a depressed McCrae penned what scholars consider to be his greatest poem – and his last, “The Anxious Dead”.

O guns, fall silent till the dead men hear

Above their heads the legions pressing on:

(These fought their fight in time of bitter fear,

And died not knowing how the day had gone.)

O flashing muzzles, pause, and let them see

The coming dawn that streaks the sky afar;

Then let your mighty chorus witness be

To them, and Caesar, that we still make war.

Tell them, O guns, that we have heard their call,

That we have sworn, and will not turn aside,

That we will onward till we win or fall,

That we will keep the faith for which they died.

Bid them be patient, and some day, anon,

They shall feel earth enwrapt in silence deep;

Shall greet, in wonderment, the quiet dawn,

And in content may turn them to their sleep.

Months after “The Anxious Dead” was published, McCrae received a historic honour: he was the first Canadian to be appointed consultant physician to the British army.

Unfortunately he was never able to accept. A life-long asthmatic and smoker, McCrae contracted pneumonia and then meningitis. He slipped into a coma and died three days later on January 28, 1918. He was 45.

Lt.-Col. John McCrae, soldier, doctor, and poet, was buried in Wimereux, France. Present at his funeral was Arthur Currie, the Canadian general who oversaw Canada’s attack on Vimy Ridge.

Ten months later, on November 11th, 1918, at 11 o’clock in the morning, the Armistice was signed. The Great War was finally over.

“In Flanders Fields” lived on after its creator’s death, inspiring millions to remember those who had died in service. After the creation of Armistice Day (now Remembrance Day), the poppy was chosen as its symbol because of this poem.

Today there exist many memorials to McCrae and his most famous work. His house stands today and is a National Historic Site. There are schools, roads, and even a mountain (in British Columbia) named after him.

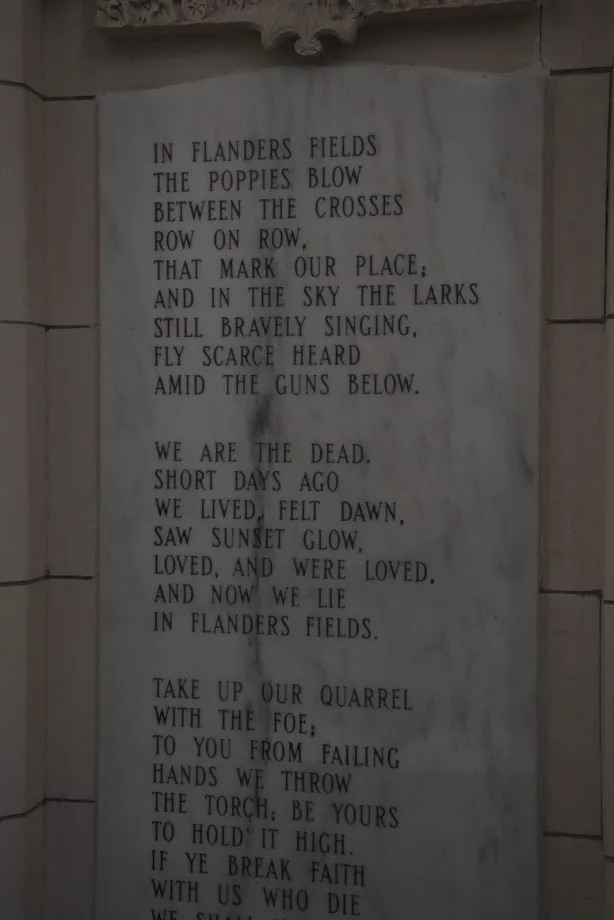

McCrae and “In Flanders Fields” are honoured in another way as well. John A. Pearson included the poem in the Peace Tower. It is mounted on a marble plaque on the back wall of the Memorial Chamber written in both English and French.

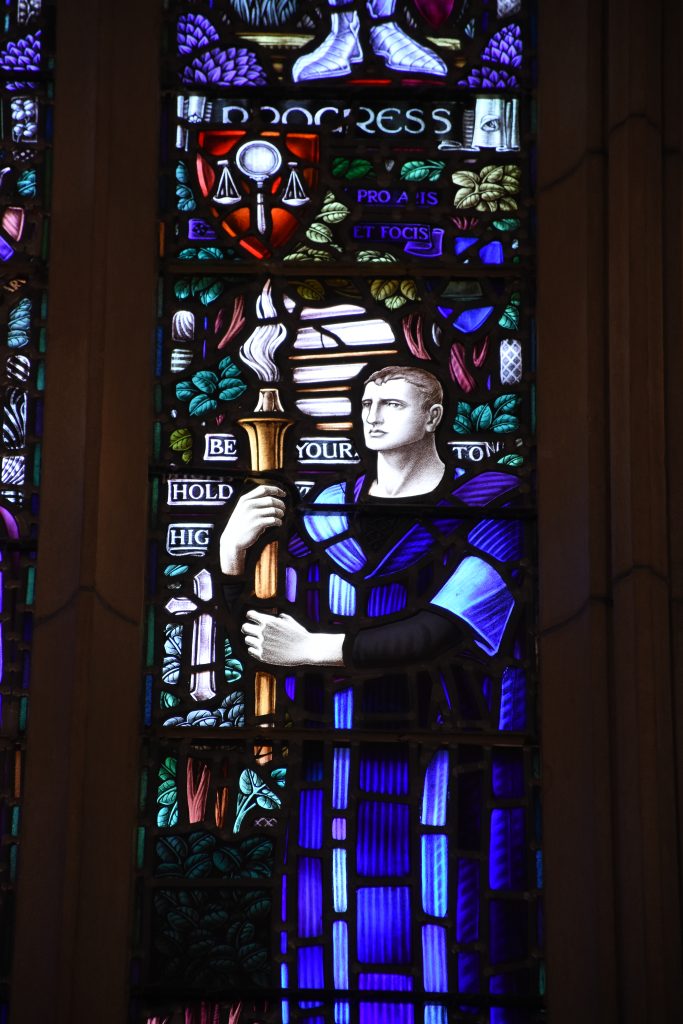

The poem is also memorialized in the stained glass window where the figure representing Honour carries a torch inscribed with BE YOURS TO HOLD IT HIGH, a quote from “In Flanders Fields”.

Remembrance Day, which is now celebrated annually on November 11, is an important part of our Canadian heritage. In the 21st century, it’s especially important to not take our freedom for granted. So we should appreciate people like John McCrae and Alexis Helmer even more for giving their lives for Canada and her future generations. Our freedom was bought by others’ blood.

This Remembrance Day, be sure to stop and remember that the freedom to do what you are doing now may be because another died.

Author’s Note: Natalie is ChristianRoots Canada’s Virtual Assistant. A homeschooled high-schooler, she loves writing, especially about Canadian history.

The Dark Ages & the French Wars of Religion Some time ago, I started to

In many places, like legislatures and schools, the Bible is considered ‘hate literature’. Counseling someone

Dominion Day had been a federal holiday that celebrated the enactment of The British North American Act which united four of Britain’s colonies – Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Upper and Lower Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec), into a single country within the British Empire, and named that country The Dominion of Canada.

Britain’s claim of Rupert’s Land by the Doctrine of Discovery, proved to be one of